1 CET School of Management, College of Engineering Trivandrum, Kerala, India

2 Recruiter-Talent Acquisition Group, Tata Consultancy Services, Uttar Pradesh, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Online technology has developed to an extent where traditional labor markets have transformed, creating opportunities for people and businesses to participate in the global marketplace by employing contract labor. Application-based transportation including ridesharing apps, food and commodity delivery platform apps, and other consumer-facing services brought in the concepts of flexible work reshaping gig work into the mainstream creating millions of jobs in the areas of operation. Even though the gig economy provides flexibility in work, the real situation of the gig workforce seems very complex. The article discusses the impacts of the gig economy on labor markets by identifying the challenges faced by gig workers in the online labor market and the impact of gig economy on their health and well-being. A detailed field research conducted among the gig workers in the state of Kerala aided examining the labor market trends, motives, and effect beyond the gig economy. It further supplemented developing specific actions to accelerate the development of the gig economy to ensure worker protection and safety needs in creating an inclusive economy.

Gig work, gig economy, gig stress, employee well-being, push-pull factors

Gig Work Economy

Technology has changed the work and labor market completely (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016) with on-demand work catching up the new normal and workers who started adapting to the changing labor market by attaching themselves to non-standard works. In the year 2008, the great recession had led the people of economically weaker sections to seek alternative ways to make a living (Katz & Kruegar, 2019). Organizations reaped benefits in hiring temporary laborers to reduce the cost of hire for full-time labor (Fisher & Connelly, 2017). The growth of the gig economy is accredited to the growth of technological, social, and economic factors in the past 50 years whereby individuals from developing countries get a scope of getting a job virtually from anywhere in the world (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016). Also, McKinsey estimated that approximately 540 million people would seek work through online talent platforms by 2025 (Woodcock, 2019). Gig work is an umbrella term that includes temporary, contingent, part-time, contract, and freelance works (Spreitzer et al., 2017; Webster, 2016). Gig economy is a trend that emerged with digitalization, a form of non-standard work mediated through online platforms with a temporary working relationship (Kuhn, 2016; Tran & Sokas, 2017), also called micro-entrepreneurship with gig workers referred to as everyday entrepreneurs (Berger et al., 2018) contracted to do micro tasks that last mere seconds.

Gig workers are hired on demand neglecting the benefits attributed to a full-time employment such as health insurance, pension schemes, and retirement benefits and only for a short period of time with no long-term contracts. There is still debate on whether gig workers should be included in the category of employees (Murray & Ball, 2016). From the gig workers perspective, minimum wage and clearer rules regarding overtime would be a great way to improve the gig economy (Farrell & Greig, 2016). Work alienation has been identified as a reason for decreased well-being, job satisfaction, job involvement, affective organizational commitment (Fedi et al., 2016), and increased emotional exhaustion (Shantz et al., 2014). Alienation is termed as the detachment from the work and workplace (Hirschfeld & Field, 2000). Gig work being online in its nature eliminates any need for the customers and employers to know the workers personally. Webster (2016) argues that due to limited available gigs, the gig workers often see each other as rivals rather than co-workers. Another related issue is the separation of gig workers from the supervisors (Harms et al., 2017). With the online nature of the gig economy, workers may be spared of various negative aspects of bad leaders, but they also lack the benefits from the positive aspects of the leader (Harms & Han, 2019). The information asymmetry with lack of explanation about work assignments often lead gig workers to believe that they are not treated fairly as an individual (Lee, 2018). Underemployment is related to various negative life and work outcomes (Allan et al., 2017). Gig workers have unpredictable working hours and comparatively lesser salary. Thus, it is argued that gig workers have precarious work situations (Ashford et al., 2018) that are uncertain and risky (Kalleberg, 2009). Gig workers often cannot predict their daily wage, making financial planning difficult, and job insecurity plays a decisive role in it. American Psychological Association (2018) conducted a survey in which 37% of the respondents believed that job insecurity is a crucial source of work stress. Thus, job insecurity was linked to lower well-being of employees. Christie and Ward (2019) conducted a survey to analyze the risk associated with the gig work and gig workers, especially drivers who do not have enough safety training and go through collisions and near misses almost every day. Young drivers, using two wheelers, are often vulnerable to accidents and affect workers beyond their workspace with negative outcomes. Even though workers have flexibility to work, they often experience constraints and risks.

In the present situation where the world has taken off with the pandemic effects, workers are seeking to find more flexible ways to work with online platforms supporting on-demand services providing freedom from employment regulations. Taking into consideration the difficulty with differences in defining and measuring the size of gig economy in the state, the research explores the critical dynamics of gig work experiences in the gig work economy in the state of Kerala. There were plenty of registered workers, but only a handful were active at a time.

Methodology

Applying a descriptive research methodology, the experience of gig workers along with the motives of being into the gig economy, subsequent risks, and challenges were studied using a structured questionnaire. The total population considered for the study includes the gig workers in the state of Kerala who have access to Internet for the survey. Simple random sampling technique is applied to collect data for a sample size of 160 gig workers using a well-structured questionnaire through social media platforms created using Google Forms.

Conceptual Model

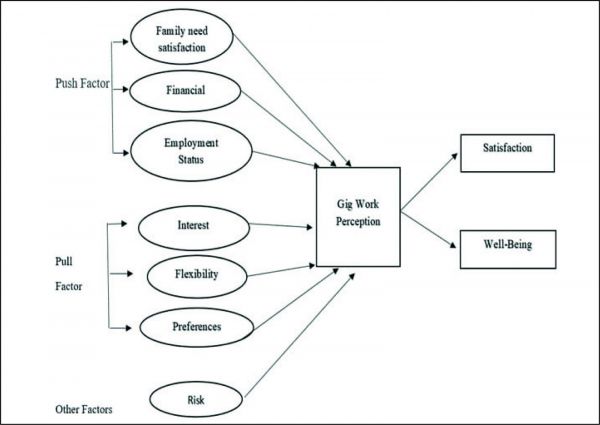

The gig economy embraces numerous youngsters undertaking gig work to meet their requirements, and the motivational factors for joining the gig economy can be classified as push factors and pull factors (Harms & Han, 2019). Push factors include all those external factors that are economically related with income deficiency, family need satisfaction, family pressure, employment status, etc., while pull factors are internal factors that depict personal preferences, values, or interests. The outcome is evaluated in terms of satisfaction and well-being as continuing with the work indicates the satisfaction level of the workers. Previous literatures show that most of the gig workers are satisfied with the work and are willing to continue the work. Along with this satisfaction, they also face various challenges. Well-being is the experience of health, happiness, and prosperity. It also includes the physical, psychological, and subjective well-being of the people involved in the gig economy as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Gig Work Perception

Analysis and Results

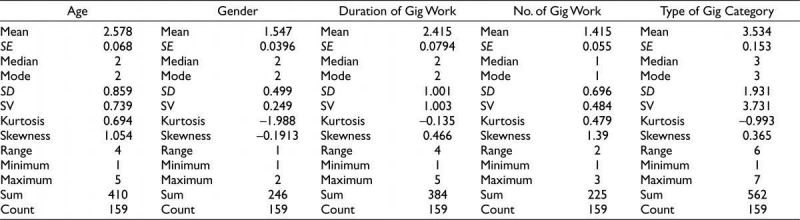

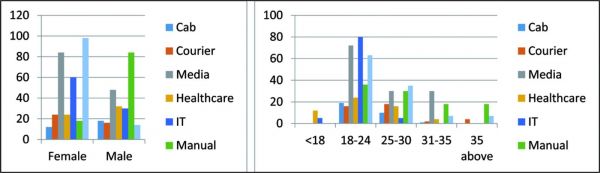

A majority of respondents (54.2%) fall in the age group of 18–24 and 30.2% fall under the age group of 25–30. Female workers contribute to 51% and male workers contribute to 47% of the sample size as shown in Figure 2. The summary of the descriptive statistics is shown in Table 1.

Figure 2. Demographics with Respect to Age and Gender Category

Source: Primary data.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

Source: Primary data.

Notes: SE, Standard Error; SD, Standard Deviation; SV, Standard Variance.

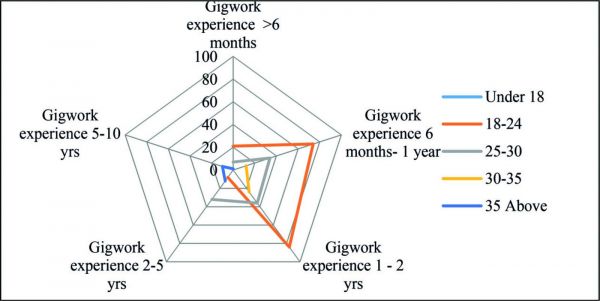

Gig workers within the age group of 18–24 are predominant in the gig work economy, ranging gig work experience from 6 months to 2 years. So, in the past two years, there was a boom in the gig economy with youth age group. Gig workers within the age group of 25–30 are having 2–5 years of gig work experience, and those who are above 30 years are having more than 5 years of gig work experience as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Age and Years of Gig Work Experience

Source: Primary data.

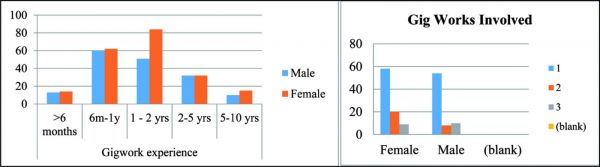

Both male and female employees are working in the gig economy, but women are found in higher numbers working in gig jobs for more than a year (Figure 4[a]). Women also have about 10 years of gig work experience. The gig workers are comparatively paid less than the permanent workers. This makes it difficult for the gig workers to meet their needs and that of their families. As a result, these workers often have to indulge in multiple gigs to meet the financial needs. It is identified that irrespective of gender, workers engage in at least three different gig work roles (Figure 4[b]).

Figure 4.(a) Gender Classification with Respect to Years of Experience in Gig Work (b) Involvement in Number of Gig Works

Source: Primary data.

Both male and female workers are involved in gig economy with a greater number of women being involved in teaching. Most of the men involved in gig work take up manual or craft work as their profession. Women are also found as most associated with gig works related to media and communications, being creative as copywriter, editor, graphic designer, musician, photography and so on, and in IT sector as well as shown in Figure 5(a). Age group of 18–24 constitutes the largest group of gig workers, of which most of the people are involved in IT sector, followed by creative, media, and communication. Age group of 25–30 is mostly involved in teaching. Most of the men involved in gig work take up manual or craft work as their profession. Men, mostly of age group 25–30, are more into on-call taxi; in media gig work, they are mostly in the age group of 18–24; and in manual or craft work such as construction worker, maintenance worker, or cleaning works, they are in the age groups of 18 and above as shown in Figure 5(b).

Figure 5.(a) Gender Classification Based on Nature of Gig Work and (b) Age-wise Classification Based on Nature of Gig Work

Source: Primary data.

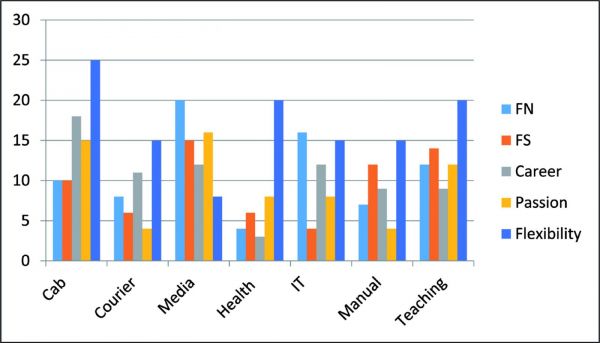

Motivational Factors Influencing Gig Work and Satisfaction in Gig Economy

“Family need satisfaction” (FN)—as an only source of income—“financial stability” (FS) by providing financial support much better than a regular job, “career prospects”, “passion” towards the nature of gig work and environment, and “freedom with flexibility” which the work offers are identified as the major motivational factors among the workers to engage in gig work and gig economy in Kerala. Based on the survey results, it is identified that most of the gig workers are motivated to join the gig economy in order to work in the area in which they see a career and are passionate about. Moreover, freedom with flexibility is identified as the major driving motivational factor to join gig economy. Survey data depicted in Figure 6 shows that for gig work role relating to cab, taxi, uber, or other on-call driver, courier, or delivery drivers, healthcare or other care workers, IT workers, manual or craft workers, and teaching jobs show higher flexibility in the gig work nature and are the driving attraction to work in gig economy. But when it comes to creative works, media, and communication work roles, meeting the family needs and passion towards such content generation works are identified as the motivating factor. Gig works in media provide more financial stability than any other gig economy followed by teaching work roles. Gig work roles in health industry do not support meeting family needs with financial stability, but IT work platforms support family need satisfaction with minimal financial stability. In manual works such as being carpenter, cleaner, construction worker, electrician, and plumber or in craft works, there is more financial stability with career prospects and flexibility. Teaching is identified as a comfortable gig work economy with motivations of financial stability, flexibility, and passion with career prospects.

Figure 6. Motivation to Join Each Category of Gig Work

Source: Primary data.

Most of the gig workers are satisfied with the kind of job they do (Figure 7). Media workers have the highest satisfaction level followed by cab drivers, tutors, manual, and IT workers. Health workers show lower satisfaction when compared to other gig economy as there can be some issues of need satisfaction or taking healthcare gig work as a career being associated with such nature of gig works.

Figure 7. Satisfaction with Gig Work Category

Source: Primary data.

Measuring the Contribution of Variables of Gig Work Towards Resulting Satisfaction

The variables of gig work include motivation to take up gig work, work career in the gig economy, gig work stress, push variables of gig work—to meet family needs and financial needs, pull variables—interest towards gig works, and flexibility, which are tested to infer whether these variables have significant relationship contributing towards gig work satisfaction.

Hypothesis 1.H0: There is no significant relationship between the variables of gig work and gig work satisfaction.

The variables of gig work and its contribution towards gig work satisfaction shows that all the variables are positively correlated, proving that there is significant relationship between the variables of gig work and gig work satisfaction as shown in Table 2. Null hypothesis is rejected, and alternate hypothesis is accepted at 0.01 level of significance.

Table 2. Correlations Between Variables of Gig Work and Its Contribution to Satisfaction in Gig Work Economy

Source: Primary data.

Note: ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Motivation to take up gig work and gig work satisfaction are moderately correlated (0.616) showing significant relation between motivational variables on gig work satisfaction. Flexibility is identifying as the most attractive motivating factor as to take up gig works either as a cab, taxi, uber, or other on-call drivers, courier, or delivery driver, healthcare or other care worker, manual or craft worker, and teaching jobs. Workers see high career prospects in gig work economy, especially with cab, courier, IT, and manual works with moderately high correlation (0.729) towards gig work satisfaction. Health workers do not find a career prospect in the healthcare gig economy, and only because of work flexibility, they show a satisfaction in the respective gig work. The ability to overcome stress is having a low correlation (0.390) with satisfaction which shows that when employees face difficulty in overcoming any stress, it will have a low impact on gig work satisfaction. Gig works in healthcare face problems of work stress. As a result, the satisfaction towards healthcare gig works is found on a lower scale.

The push factors of gig work, gig work roles meeting family needs, and ability to meet financial needs are positively correlated with gig work satisfaction with low correlation values of 0.473 and 0.382, respectively. Gig work in media—to a very large extent—IT, and teaching support meeting family needs and offer financial stability. And gig works such as cab driver, courier, and manual work moderately support in meeting family needs and extend financial stability, but being into healthcare gig economy poorly supports in meeting family needs with minimum financial security. The work being temporary in nature, the workers often are at a risk of not being able to find a new gig, task, or role. These factors together push workers away from the gig economy.

The pull factors, on the other hand, pull people towards the gig economy. The first factor is interest; most gig workers choose gig works out of interest to work in the field they are interested in, and the correlation results show that there is a high positive correlation (0.807) between interest in taking up gig work and its resultant satisfaction. Being able to work in their area of interest helps workers be motivated and work stress-free. Another factor is flexibility, and gig workers enjoy extreme temporal flexibility by which they can choose how to spend each hour and minute of the day. Test results of correlation between flexibility that gig work provides and satisfaction of workers are positively correlated with a correlation value of 0.65, showing that the gig economy has a flexible labor market that allows flexible working hours, short-term contracts, shift-based work, home-based work, etc. For gig works in media and communication industry, workers do not find work flexibility as the attractive variable, instead meeting financial needs, passion, and career prospects promotes the media gig economy. Preference is another factor that pulls people into gig works. There are more general pull factors that pull people into the gig economy, as many educated but unemployed youth in the nation often prefer gig works, even at the cost of being underemployed. The growth of gig economy is highly evident that is supplemented with the online platforms providing people a means of living, pulling them into the gig economy.

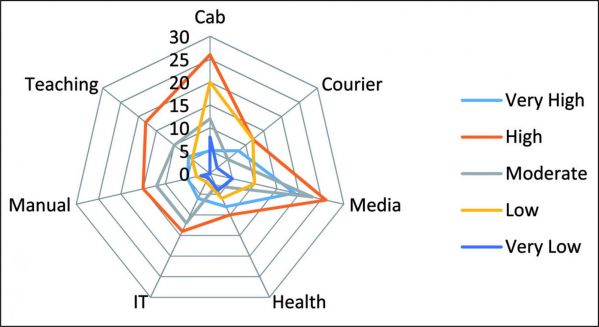

Risks in Gig Economy and Satisfaction Towards Gig Work

Hypothesis 2.H0: There is no significant relationship between the risk associated with gig work and gig work satisfaction.

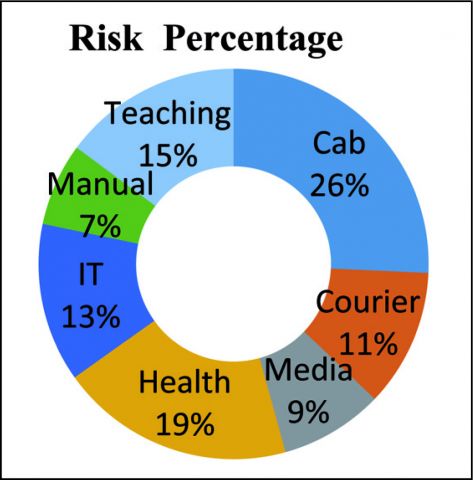

Result of correlation between risk involved in gig work and satisfaction shows that there is a very low correlation (0.138) between the variables as shown in Table 3. Some gig works are too risky making the respective gig work less impressive with less satisfaction. Most of the gig workers accept the fact that there is risk associated with the gig work. As shown in Figure 8, survey results make it clear that the highest risk is faced by cab and taxi drivers (26%), follwed by healthcare workers (19%), teaching (15%), IT (13%), courier (11%), media (9%), and manual works (7%). It is seen that when there is higher flexibility in the type of work, then there would usually be the potential of risk which can be sorted as personal risk as gig work provides an unstable form of unemployment.

Table 3. Correlations Between Risks and Gig Satisfaction

Source: Primary data.

Figure 8. Percentage Risk of Gig Work Category

Source: Primary data.

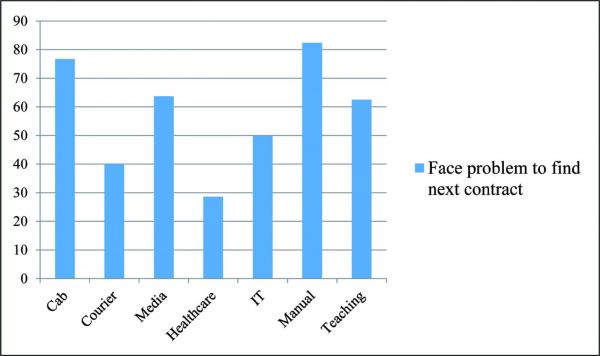

Survey results also show that the workers who work in gig works related to courier and other delivery works, media, IT, and teaching receive an adequate amount of training. Cab drivers, healthcare workers, and manual workers do not receive enough training on their respective works and often have to break the traffic rules to meet the deadline many a times. Cab drivers and two-wheeler delivery workers are more prone to accidents as these gig workers are never given training by the organization which employs them on a short-term contract. Media workers, even though they are trained and have the required skill sets and passion, also had to break the traffic rules to meet the deadline which can result in work stress and is eventually risky. Gig workers related to tutoring are the only people who have received perfect training and are passionate to finish the work on time with satisfaction. Survey results, as shown in Figure 9, also confirm that workers find it difficult to find the next contract, task, or gig work once the short-term contract expires. This mode of work on temporary basis will increase the risk in each gig economy, and the highest percentage of difficulty to find the next gig work is for manual and craft economy (82%), followed by cab drivers (77%), media workers (62%), tutors (61%), IT (50%), courier (40%), and healthcare workers (29%). The research also clarifies that when flexibility of work is higher, it is more difficult to find the next gig economy work once the contract gets expired.

Figure 9. Percentage Difficulty in Finding the Next Gig Work

Source: Primary data.

Most workers in today’s gig economy find themselves in a position quite different from that of the regular employed workers. Lower wages and underemployment create pressure to hold gig works. But exceptionally high-skilled workers are becoming the epitome of happy gig worker status and contribute towards the heightened boom in gig economy. Companies typically provide little training to gig workers because of the unstable nature of employment with the workforce changing constantly. As a result, many gig jobs are low skilled, and tasks that require expertise demand permanent and trained workforce.

Impact of Gig Work on Worker Satisfaction and Well-Being

Regression analysis is carried out to identify the impact of gig work economy on worker satisfaction and well-being with dependent variables as motivation to take up gig work and gig work satisfaction and risks in gig work as an independent variable as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Regression Model Summary

Source: Primary data.

Notes: a. Predictors: (Constant), Risk, Satisfaction. b. Dependent variable: Motivation.

Hypothesis 3.H0: Gig work and outcome on working with the gig economy are independent.

The p-value obtained (.000) is less than the significance level of 0.05, providing enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis for the entire population. Motivation (dependent variable) and the factors motivating to take up gig work and to be in the gig economy are associated with gig work satisfaction and corresponding risks in the nature of gig work (independent variables) with a reliability of 61.7% and R2 value of 0.380, proving that the test results are statistically significant at the population level. Alternate hypothesis is accepted, establishing that gig work and outcome on working with the gig economy are dependent.

Concluding Remarks on Worker Well-Being in the Gig Economy

The gig economy is one of the most fascinating work-based trends in recent years. Even though gig workers lacked the stability and benefits of full-time workers, they were significantly happier when they had control over their schedules and with the jobs they took on. This research article made an attempt to identify the motivational factors to join a gig economy and found that factors such as interest towards the job, preference, and flexibility act as pull factors towards gig work and workers who join gig economy out of their own interest for a particular job enjoy more work satisfaction. Also, the flexibility in the working hours and job roles help workers to work without stress (Baltes et al., 1999). Personal preferences, interests, and values are more likely to result in positive outcomes such as higher levels of well-being and perseverance in the gig economy. Push factors, namely financial, family need satisfaction (Wilensky, 1963), and employment status de-motivate the employees to continue in gig work roles, and moreover, lack of financial stabilities often increases the stress level of the workers.

The research done among gig workers in the identified gig sectors establish that there are certain risks associated with each gig work, especially in logistics of cab drivers and delivery boys encountering accidents due to lack of training in meeting delivery time (Scheiber, 2017). They also find it difficult to get the next contract once the existing contract expires (Parker et al., 2017). Healthcare workers often face the “risk and reward” pattern, face risk with respect to the nature of work and instability in the employment, and often encounter risk such as difficulty in finding the next gig work. Media workers are often well trained and passionate about their work, but they too often have to break the traffic rules so as to meet the deadlines and encounter difficulty to find the next gig work, especially in terms of continuity. But highly skilled and richly experienced creative workers do not face much difficulty and do not enjoy much flexibility in the work role. Manual workers often lack training as per the survey data and take up gig work to support their family and satisfy their needs. Risk in terms of health and safety is minimum, but it is this category of gig workers who face the highest difficulty to find the next gig work. Teaching is probably the gig with moderately attached risk in terms of health and safety and in terms of difficulty level to find the next gig work in the respective field.

To address the problems in the gig economy, the government should take steps to prevent insecure working conditions supporting equitable business models by creating policies to help gig workers to overcome the financial obstacles. Health and safety requirements, similar to institutionalized workplaces, are needed in the gig work economy. Increasing mental health awareness amongst the general public is much appreciated with focus on stress eradication to provide a sense of well-being in the gig economy. Conducting proper trainings for the gig workers, particularly the cab drivers and delivery workers, will help reduce accidents and motivate workers to meet their deadlines and targets (Bajwa et al., 2018). Gig economy will surely benefit businesses and consumers, but it happens only at the cost of workers. Future research can be taken up for identifying ways to ensure greater stability to protect workers in the gig economy.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

American Psychological Association. (2018). Work and well-being survey.

Allan, B. A., Tay, L., & Sterling, H. M. (2017). Construction and validation of the subjective underemployment scales (SUS). Journal of Vocational Behavior, 99, 93–106.

Ashford, S. J., Caza, B. B., & Reid, E. M. (2018). From surviving to thriving in the gig economy: A research agenda for individuals in the new world of work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 38, 23–41.

Bajwa, U., Gastaldo, D., Di Ruggiero, E., & Knorr, L. (2018). The health of workers in the global gig economy. Globalization and Health, 14(1), 1–4.

Baltes, B. B., Briggs, T. E., Huff, J. W., Wright, J. A., & Neuman, G. A. (1999). Flexible and compressed workweek schedules: A meta-analysis of their effects on work-related criteria. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(4), 496.

Berger, T., Frey, C. B., Levin, G., & Danda, S. R. (2018, October). Uber happy Work and well-being in the “gig economy”. https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/201809_Frey_Berger_UBER.pdf

Cascio, W. F., & Montealegre, R. (2016). How technology is changing work and organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3, 349–375.

Christie, N., & Ward, H. (2019). The health and safety risks for people who drive for work in the gig economy. Journal of Transport & Health, 13, 115–127.

Farrell, D., & Greig, F. (2016). Paychecks, paydays, and the online platform economy: Big data on income volatility. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Institute.

Fedi, A., Pucci, L., Tartaglia, S., & Rollero, C. (2016). Correlates of work-alienation and positive job attitudes in high-and low-status workers. Career Development International, 21(7), 713–725.

Fisher, S. L., & Connelly, C. E. (2017). Lower cost or just lower value Modeling the organizational costs and benefits of contingent work Academy of Management Discoveries, 3(2), 165–186.

Harms, P. D., Credé, M., Tynan, M., Leon, M., & Jeung, W. (2017). Leadership and stress: A meta-analytic review. The Leadership Quarterly, 28, 178–194.

Harms, P. D., & Han, G. (2019). Algorithmic leadership: The future is now. Journal of Leadership Studies, 12, 74–75.

Hirschfeld, R. S., & Feild, H. S. (2000). Work centrality and work alienation: Distinct aspects of a general commitment to work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 789–800.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74, 1–22.

Katz, L. F., & Krueger, A. B. (2019). The rise and nature of alternative work arrangements in the United States, 1995–2015. ILR Review, 72(2), 382–416.

Kuhn, K. M. (2016). The rise of the “gig economy” and implications for understanding work and workers. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 9(1), 157–162.

Lee, M. K. (2018). Understanding perception of algorithmic decisions: Fairness, trust, and emotion in response to algorithmic management. Big Data & Society, 5(1), 1–16.

Murray, N., & Ball, T. (2016). The gig economy and the U.S. labor system. Labor and Employment Law, 44(3), 1–2.

Parker, S. K., Morgeson, F. P., & Johns, G. (2017). One hundred years of work design research: Looking back and looking forward. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 403.

Scheiber, N. (2017). How Uber uses psychological tricks to push its drivers’ buttons. The New York Times, 2.

Shantz, A., Alfes, K., & Truss, C. (2014). Alienation from work: Marxist ideologies and twenty-first-century practice. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(18), 2529–2550.

Spreitzer, G. M., Cameron, L., & Garrett, L. (2017). Alternative work arrangements: Two images of the new world of work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 473–499.

Tran, M., & Sokas, R. K. (2017). The gig economy and contingent work: An occupational health assessment. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 59, e63.

Webster, J. (2016). Microworkers of the gig economy: Separate and precarious. New Labor Forum, 25(3), 56–64.

Wilensky, H. L. (1963). The moonlighter: A product of relative deprivation. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 3(1), 105–124.

Woodcock, J. (2019). The impact of the gig economy. In Work in the age of data. BBVA. https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/articles/the-impact-of-the-gig-economy/