1 Department of Commerce, Netaji Nagar Day College, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

2 Department of Economics & Statistics, University of Mauritius, Reduit, Mauritius

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

India and Mauritius have important historical and cultural ties, and trade, investment and strategic exchanges between them. India is the sixth-largest investor in Mauritius, while Mauritius is the third-largest investor in India. However, because of the Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA) with India and the concurrent lack of a capital gains tax in Mauritius, a sizeable amount of the capital flows from India to Mauritius were essentially round-tripping or fiscal evasion of taxes on Indian money. The majority of Indian businesses that do business in Mauritius do not have any manufacturing or trading facilities. In light of this, the current work makes an effort to conduct a qualitative case study utilising primary and secondary data to follow the development of the strategic investment ties between India and Mauritius through money migration, after the DTAA was amended in 2016. After 2018, China has surpassed India in terms of volume of capital investment into Mauritius, with Singapore emerging as the largest provider of foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows into India. The study observes that this shift in trend is not the result of only the treaty being amended but also the tax morale of the respective countries as well as the invasive economic policy of China. Whatever legal changes are made, if human avarice is not restrained, dishonest people will always find clever ways to circumvent the law to further their agendas.

Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA), fiscal evasion of taxes, foreign direct investment (FDI), India–Mauritius investment ties, qualitative case study

Introduction

The concepts of sovereignty and its equality form the foundation of the contemporary state structures. Keeping in alignment with the global governance requirements, every state is free to enact laws and establish its own regulations including those pertaining to taxes, in favour of their domestic interests (Genschel & Schwarz, 2011; McCaffery, 2005; Nerré, 2001). The citizens and corporations have an obligation to pay taxes to their government; nonetheless, there is a propensity to evade and avoid taxes among them. Tax mitigation is both legal and ethical, tax avoidance through prudent tax planning is within the boundaries of law though not desirable, while fiscal evasion is completely illegal and punishable (Molero & Pujol, 2011; Pickhardt & Prinz, 2014). In this context, tax havens, or countries offering significantly low or zero tax rates to the foreign investors, are not a new phenomenon. The basic premise of the development of such jurisdictions lies in the tax-resistant attitude that can be traced back to the second-century bc civilisations in the eastern Mediterranean (Raposo & Mourão, 2013). A modern analogy can be drawn from the eighteenth-century legend of the Cayman Islands, the residents of which do not need to pay any taxes even today (Oakley, 2017). Presently, close to 75 countries are earmarked as tax havens of the world, including the USA, the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland for their effectiveness of concealing financial information and identity of the investors from foreign authorities (List of the World’s Most Notorious Tax Havens, 2024). Large multinational corporations (MNCs) with intensive research and development activities are found to leverage the tax havens to siphon off their earnings from high-tax jurisdictions to ensure higher growth as compared to their non-tax haven competitors (Desai et al., 2005). They incessantly restructure and reorganise their operations and investments to ‘shop’ tax and investment treaties across the globe. Almost 30% of the global foreign direct investment (FDI) is found to be indirect, or stated otherwise, it is merely ‘the flow of domestic funds channelled through offshore centres back to the local economy in the form of direct investment, also known as foreign direct investment round tripping’ (Aykut et al., 2017).

In the case of indirect FDI, MNCs invest in a host country through one or more intermediate companies in a third country. In this form of FDI, the nationality of the direct investor, which in most of the cases is a financial company, does not match with the carefully concealed final beneficiary. Hence, many times the funds are actually domestic, which has been routed through an intermediate financial entity in a country with low rates of tax, lenient tax rules, flexible corporate governance and indulgent FDI norms. The deliberate blurring of the identity of the true investor jeopardises policy formulation, financial performance and status assessment of the host economy. Such investments do not constitute any real industrial activity, instead increases volatility of investment due to the lack of their long-term business direction. They behave more like a foreign portfolio investment (FPI), instead of an FDI. This obviously leads to losses in both tax revenue as well as welfare in the home country, and as a consequence, the perceived developmental benefits of FDI in terms of capital injection, employment generation and technology diffusion fail to percolate through the host country.

In 1998, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) issued guidelines for combating the menace of the round-tripping of FDI and to prevent treaty shopping, fraudulent activities and financial crimes across the world (Jackson, 2010; OECD, 1998). Additionally, in 2002, OECD published the Model Agreement on Exchange of Information on Tax Matters (TIEA model) and its Commentary to specify the provisions pertaining to exchange of financial information between the partnering nations. These initiatives later culminated into the current version of the Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA), which refers to an agreement under which taxpayers residing in one country and earning their income from another country do not require to pay tax on the same income in both the countries (Nalsar University of Law Editorial Team, 2023; Sabnavis & Sawarkar, 2016). To bridge the legal loopholes, the General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAAR) and the Limitation of Benefits (LoB) clause were subsequently introduced in 2017 to prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). However, in spite of so many initiatives, the prevention of fiscal evasion could not be guaranteed (Shukla, 2021).

A substantial corpus of literatures discuss on the concept of tax havens, causes behind their creation, how they are poaching off the tax bases of non-haven economies leading to fiscal shortfalls and posing as a challenge to the international tax regime and what could be done to combat them, including the implications of the Mauritian route of investing into India (Aykut et al., 2017; Chernova, 2022; Desai et al., 2006; Genschel & Schwarz, 2011; Gunputh et al., 2017; Jalan & Vaidyanathan, 2017; Pitkänen & Ronnerstam, 2021; Raposo & Mourão, 2013; Rosenzweig, 2010; Shaxson, 2011; Yadav, 2018). Nonetheless, not many researches has been conducted on the evolution of Indo–Mauritian investment relationship and its current status post-amendment of the DTAA between India and Mauritius during 2016–2017.

Trade, investment and strategic exchanges between India and Mauritius are of significant value. The countries have significant historical and cultural connections as well. Mauritius receives substantial investment from India in the form of equity, debt, lines of credits and guarantees issued. India is the sixth-largest investor in Mauritius (Bank of Mauritius, 2023). From July 2007 to June 2023, Mauritius received FDI inflows worth USD 72,783.86 million which is 15% of the total outward FDI from India. The small island state Mauritius, on the other hand, was the biggest source of FDI inflows into the Indian subcontinent till 2017. It accounted for 29.07% of the total FDI inflows into India during 2000–2022 (Reserve Bank of India, 2023). It is apprehended that a large portion of the capital flows from India to Mauritius are actually round-tripping or fiscal evasion of taxes on Indian money (Ali et al., 2022; Gunputh et al., 2017; Jalan & Vaidyanathan, 2017; Thukral, 2022) due to the existing DTAA signed between India and Mauritius on 24 August 1982 and the simultaneous absence of capital gains tax in Mauritius.

In this context, the objective of the present study is to undertake a qualitative case study to trace the evolution of the Indo–Mauritian strategic exchange through migration of funds, especially post-amendment of the DTAA in 2016–2017. The study endeavours to bridge the current research gap by not only examining the success or failure of the fiscal corrections, but also attempts to trace the regional geo-political influences and the behavioural aspects behind the flow of FDI between the nations.

This case study is structured in the segments as follows: the first section discusses the relevant literatures about globalisation, FDI and fiscal evasion. The second section outlines the research methodology. The third section discusses the findings in three sub-parts, namely, the journey of Mauritius towards becoming a tax haven, the procedural aspects of round-tripping of Indian investment through the Mauritian route and the status of Indo–Mauritian investment post-amendment of the DTAA and the reasons thereof; and the last section of the article concludes.

Literature Review

Globalisation and Tax Havens

Globalisation has three dimensions: the economic aspect, the political aspect and the cultural aspect. The history of the development of tax havens is connected with the expansion of economic globalisation, first, with the spread of capitalism during the nineteenth century and second, post-World War II, with the manifold increase of the cross-border flows of goods, services, labour and capital and the formation of the eurodollar market led through deregulation and liberalisation of the economies (Pitkänen & Ronnerstam, 2021). In the opinion of Todaro and Smith (2020), the efficiency and effectiveness of the tax collection mechanism of a host economy depends a lot on the political will of the government. When few corporations succeed to cunningly reduce or manipulate their compulsory tax payments, the rival firms tend to lose on competition which forces them to take the same approach to stay in competition (Pitkänen & Ronnerstam, 2021).

There are a number of literatures on how the wealthiest people, corporations and countries reached their status through tax evasion and money laundering. Nicholas Shaxson (2011) in his famous book ‘Treasure Islands: Tax havens and the men who stole the world’ commented that ‘tax havens …. are the ultimate escape routes for our wealthiest citizens and corporations from a menagerie of laws, rules, financial regulations and democratic accountability. Offshore is globalization’s rotten core’. According to him, ‘colonialism left through the front door, and came back in through a side window’ in the name of globalisation. Revelation of the Panama Papers (2016), Paradise Papers (2017), Pandora Papers (2021) and many such financial leaks by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) brought to the fore the unaccounted-for financial information of a significant number of corporate giants, global leaders, politicians, public officials, High Net worth Individuals (HNIs), sport stars and celebrities (BBC News, 2021). They used the different tax havens for money laundering and channelising their illicit funds.

Today, the tax havens and offshore financial centres (OFCs) are both the recipients as well as the originators of almost 30% of the world’s share of FDI. The Bank for Financial Settlements finds that almost 50% of the cross-border flow of funds from increasingly varied sources gets routed through tax havens (Raposo & Mourão, 2013). Pitkänen and Ronnerstam (2021) find a significant positive impact of economic globalisation on the prosperity of the tax havens. According to Manish and Soni (2020), because laws are enforced at the national level, the freedom that comes with globalisation is largely misused.

Foreign Investment and Tax Havens

The taxation rules have a significant bearing on the quantity and quality of international flow of funds into the host economy. In case of international business, due to the involvement of more than one country, the resident of a certain country may have earnings generated in some other country. Today’s highly sophisticated and complex global value chains and ownership structures of the MNCs with numerous cross holdings and affiliates make it challenging to categorise and monitor them by their home and host country status. Channelling funds through low-tax jurisdictions instead of the home countries does not necessarily imply an illegal act. Treaty shopping might result in a considerable 6% point average reduction in tax burdens of the MNCs without the indirect routing of the repatriated income. The coefficients of the treaty shopping indicators are found to be statistically robust and significant, exerting economic influence on bilateral FDI stocks (Van’t Riet & Lejour, 2018).

Low- or zero-rate tax havens are not significant conduit nations. There is a possibility that under-developed nations where resources and wealth are distributed unequally can maximise welfare in a world with low tax rates (Rosenzweig, 2010). Notably, majority of the tax havens are small island developing states (SIDS) having paucity of natural wealth and financial resources, and thus, are largely dependent on foreign trade, investments, grants and aids (Manish & Soni, 2020). They make capital allocation more effective and foster international tax competition. This pushes for more economic discipline and better fiscal policies throughout the rest of the world (Mitchell, 2006). The founder of the first offshore company in the new Mauritius Offshore Business Activities Authority regime in 1993 believes that instead of resenting the loss of tax revenue on capital gains in India, celebrations should be made for the increased gains in other direct taxes such as corporate, dividend and employment taxes, and indirect taxes due to increased economic activity brought about by FDI facilitated by the India–Mauritius treaty (Desai & Sanghavi, 2008). However, corporate misreporting or under-reporting or concealment of material facts and information with an ulterior motive of tax evasion is an illegal act, and a matter of greater concern.

Fiscal Evasion of Taxes

Jones and Temouri (2015) adapted a ‘firm-specific advantage-country-specific advantage framework’ and identified that the home-country corporate tax rate had the least impact on an MNCs decision towards setting up of a tax haven subsidiary; instead, the nature of capitalism and intensity of technology existing in a home-country location appeared to be a much stronger determinant. On the contrary, Maffini (2009), Dyreng and Lindsey (2009) and Jaafar and Thornton (2015) found that the marginal effective tax rates of MNCs having tax haven subsidiaries have been found to be notably lower as compared to their rivals with only non-tax haven subsidiaries making tax haven subsidiaries a popular and convenient alternative. Additionally, tax haven operations were found to positively influence the neighbouring non-tax haven activities (Desai et al., 2005).

Tax evasion may be encouraged or prevented by behavioural dynamics (Pickhardt & Prinz, 2014). The tax morale of a nation plays a decisive role in tackling tax evasion problem by MNCs. Countries with low tax morale are found to take resort to round-tripping of domestic funds through tax havens for tax evasion (Kemme et al., 2019). The level of tax morale, however, depends on individual as well as governance factors. The degree of trust and satisfaction with the government and its quality of public services influence the tax morale of the residents (Daude et al., 2013). The MNCs interact with the home-country tax laws depending on the effectiveness of tax evasion prevention measures, the practices of the rivals and the strength of its own social welfare logic (Nebus, 2019).

In the Indian context, it was expected that after the amendment of the stated DTAA in 2016, the quantity and quality of trade as well as capital flows between India and Mauritius shall witness a transformation. Kotha (2018) evaluated the roles of the executive, legislative, judicial and quasi-judicial authorities, the tax authorities and the revenue officers of India in the movement of Indian entities to Mauritius between 1983 and 2017. Mathur et al. (2015) observes that FDI from tax havens like Singapore and Mauritius may be impacted by the tax treaties with India like the DTAA, regulations like the GAAR, and the LoB clause. If India keeps up the DTAA with these tax havens, it will lose out on tax revenue; however, if it implements GAAR, it will lose out on FDI flows from these nations. In the given context, the present study attempts to make a fact check about the reality of FDI inflows into India from the Mauritius post-amendment of the DTAA in 2016.

Methodology

The study is a qualitative case study exploring both primary and secondary data. The secondary data on FDI flows were collected from the websites of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Bank of Mauritius for the period of July 2007 to June 2023. Other pertinent information was assimilated from the company websites, annual reports and other online materials including journals, book chapters, reports and blogs.

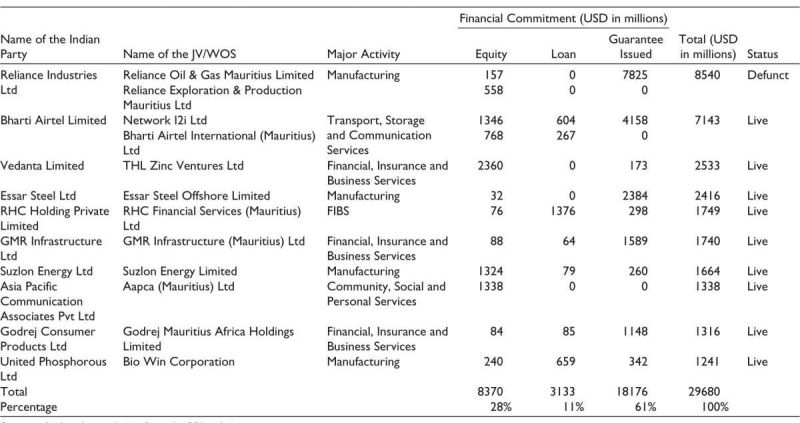

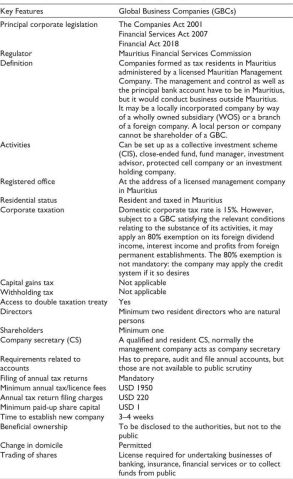

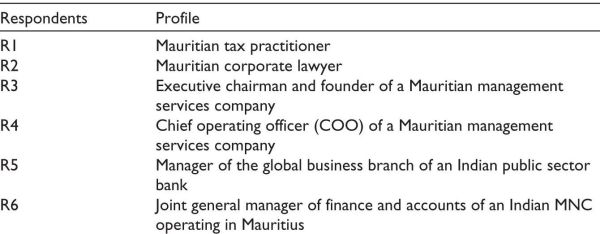

For procuring primary data required for the analysis an attempt was made to conduct personal interviews with the authorised personnel of the companies mentioned in Table 1. However, it was found that a majority of these Indian companies do not have any manufacturing, services or trading set up in Mauritius; instead they operate as Global Business Companies (GBCs) (Table 2) which are formed as tax residents in Mauritius administered by a licensed Mauritian management services company either as a collective investment scheme (CIS), close-ended fund, fund manager, investment advisor, protected cell company or as an investment holding company. Such GBCs are committed to maintain secrecy of their clients and their operations lack transparency. Hence, availability of data as well as respondents became a critical challenge. Nonetheless, few professionals unrelated to these companies assented to be interviewed anonymously (Table 3). The interviews, in person and over the telephone, were conducted using non-directive unstructured questionnaire. Their responses were analysed using inductive thematic analysis method propounded by Braun and Clarke (2006).

Table 1. Top Ten Indian Companies Investing in Mauritius From July 2007 to June 2023.

Source: Authors’ compilation from the RBI website.

Table 2. Key Features of Global Business Companies (GBCs).

Source: OCRA Worldwide Mauritius (2020) and Arch Global Consult (2020).

Table 3. Profile of the Respondents.

Findings and Discussion

Mauritius: Journey Towards Becoming a Tax Haven

Mauritius is a very small tropical and volcanic island on the Indian Ocean with a population close to 1.28 million. It is a natural-resource-deficient country and therefore, largely dependent on foreign trade, investment and grants. The main pillars of the economy are tourism, textile and financial services. As located at the heart of the Indian Ocean, Mauritius enjoys strong trade and investment ties with Africa, south and South-East Asia and Australia. Being a European colony till its independence in 1968, it has strategic affinity to the European countries as well (Bowman, 2023).

Prior to her independence from British rule, Mauritius was primarily a sugarcane-based monoculture and an unindustrialised economy with prolonged balance of payments (BoP) deficits. Sugar constituted 35% of the aggregate domestic production and 98% of the total exports under the Commonwealth Sugar Agreement (CSA). High exposure to trade shocks, inequality in distribution of income, unemployment induced by population explosion, political unrest and social protests led the Nobel Laureate economist James Meade to consider Mauritius getting engulfed into the ‘Malthusian trap’ of over-population (Meade, 1967). However, post 1970s, the government took initiatives to diversify the economy by promoting manufactured exports through the setting up of the export processing zones (EPZs), which were largely fed by the FDI inflows. It also started stimulating the travel and tourism sector besides the predominant agricultural sector. This resulted in spillover effects through enhanced productivity, heightened domestic investment and augmented exports. Complementary public-private partnerships through setting up of institutions such as Mauritius Investment Development Authority (MIDA), Export Processing Zones Development Authority (EPZDA) and Small and Medium Industries Development Authority (SMIDA) catalysed the popularity of Mauritius as an investment destination. These together moved Mauritius up the global value chain which won the country the accolade of ‘Economic Miracle’ given by the World Bank in 2002 (UNIDO, 2021).

In the second phase of industrialisation after 2000, the telecommunications sector and the financial services sector were popularised in Mauritius. Several bilateral investment treaties (BITs), legislative changes and membership in regional associations like the South African Development Community (SADC), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) and Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Cooperation (IOR-ARC) helped Mauritius regain its economic growth in this phase as well (Sooreea-Bheemul & Sooreea, 2012).

According to the World Happiness Report 2023, Mauritius is the happiest country in the African subcontinent and the 59th happiest country out of the 149 countries across the world with a happiness score of 5.9 (World Happiness Report, 2023). The Legatum Prosperity Index places Mauritius as the 47th prosperous nation of the world (out of 167 nations) (Mauritius: Legatum Prosperity Index 2023, n.d.). Mauritius stands at a Global Rank of 13 and is the best performer in sub-Saharan Africa in terms of the Ease of Doing Business Index 2020 with a remarkable score of 81.5 (The World Bank, 2020). However, according to the Sustainable Development Report 2023, Mauritius has a corporate tax haven score of 81 against a standard 40 which signifies that the country poaches off tax bases of other nations based on its laws, rules and recorded administrative practices (Mauritius: Sub-Saharan Africa, 2023). Out of the four categories of tax havens, namely Western colonies, sovereign nations, nations as part of cartels and emerging economies, Mauritius comes under the fourth category, as the tax haven status leaves the SIDS with quality education, employment generation, strong governance, development of the financial sector and growth in public revenues (Raposo & Mourão, 2013). Mauritius is used as a tax-efficient vehicle by global investors to minimise the withholding tax of dividends, interests and royalties and also as a platform to invest in Africa. To attract foreign investments, Mauritius offers several incentives to foreign investors, which in turn has marked Mauritius as a tax haven country. Mauritius has signed 44 DTAAs, 45 Investment Promotion and Protection Agreements (IPPAs) and 49 Memorandum of Understanding (MoUs) with different countries across the globe (Economic Development Board Mauritius, 2021). Companies formed to access the Mauritian network of DTAAs as tax residents in Mauritius, ensured that it is correctly structured and the seat of management and control is in Mauritius and administered by a licensed Mauritian Management Company. Foreign companies are permitted to operate from Mauritius as Mauritius authorised companies (ACs) and GBCs. It is to note that previously GBCs were taxed at 15% with a rebate of 80% making the effective tax rate to be a mere 3%. Presently, the flat tax rate for all Mauritian tax-resident companies has become 15%. However, a partial exemption of 80% is still received on certain incomes. In the opinion of R3,

Mauritius has uniquely placed herself as the only investment grade international financial centre (IFC) in sub-Saharan Africa to drive trade and investment in mainland Africa, and to develop solutions in partnership with mainland Africa for shared economic growth. Through her signing of Comprehensive Economic Cooperation and Partnership Agreement (CECPA) with India and Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with China, Mauritius has a central role to play in facilitating trade and investment between Asia and Africa, and within Africa.

Modus Operandi: How It All Happens

According to R6,

The economic sustainability of the tax havens hedges on maintaining unobtrusive Know-Your-Customer (KYC) norms. The sovereign governments consider them as a threat to their fiscal gains, while the MNCs and High Net worth Individuals (HNIs) take their aid to shred off their tax burdens.

India has a total of 94 (PwC, 2024) and Mauritius 44 DTAAs (EDB Mauritius, 2022) with different countries of the world. In absence of such treaties, investors may not consider investing in host economies due to the apprehension of the same income being taxed twice in two different countries (Pitkänen & Ronnerstam, 2021). Mauritius is a well-documented round-tripping corridor for India, operating through OFCs. OFCs or GBCs or special purpose enterprises (SPEs) have the capability to opaque the real source and true nature of FDI. India and Mauritius had an operational DTAA prior to the Mauritian independence in 1968. A new comprehensive DTAA came into force between India and Mauritius on 1 April 1983.

According to R4, ‘Mauritius acted as a platform for India to enter the vastly unexplored African market. It was part of a few regional African trade blocks, and had preferential trade agreements and DTAAs with many African countries which India had not’. Moreover, capital gains were taxed solely at the country of residence (Desai & Sanghavi, 2008). Hence, a paradigm shift took place when India liberalised in 1991 and simultaneously, in 1992, Mauritius entered into the second stage of industrialisation by aiming to become a non-banking offshore investment jurisdiction. The prospective foreign investors identified the enormous possibility of tax arbitrage while investing in India through Mauritius. Mauritius became the most preferred route for entering into the Indian economy, one of the most lucrative investment destinations of that time, in the form of both FDI and FPI inflows. The ‘Mauritius Tax Residency Certificate’ issued by the Mauritius Tax Office was accepted as a valid evidence of tax residency of such companies and ignored the beneficial ownership of the entities (Kotha, 2018). Moreover, the corporate tax rate was substantially higher in India vis-à-vis the Mauritian corporate tax rate applicable to offshore companies (currently, the corporate tax rate of India ranges from 25% to 30%, excluding surcharge), and there was no exchange control on the exchange rate of Mauritian currency leading to transactions of unlimited value.

R1 commented that

The biggest imperative to invest in India through Mauritius was that an OFC resident at Mauritius need not pay any capital gains tax on divestment of its securities, while direct investment and its subsequent disposal attracted 30% capital gains tax in India.

In the opinion of R5,

As a consequence,

a. Foreign investments to India started getting routed through Mauritius for the sake of better tax management

b. Indian companies started setting up ‘shell companies’ using complex MNC structures to avoid tax.

c. The entities ended up with non-payment of taxes in either of the countries, leading to double non-taxation.

On record, 713 Mauritian companies received FDI inflows from India during July 2007 to June 2023. Out of them 580 (81%) companies are wholly owned subsidiaries (WOS) of Indian companies. The rest 133 (19%) companies have entered into joint venture (JV) agreements with their Indian counterparts; 13 Mauritian companies have received FDI inflows worth more than USD 1 billion from India during the stated period: 52% of the total financial commitment from India came in the form of guarantees issued, 32% as equity and the rest 16% as loan (Reserve Bank of India, 2023).

The revision of the treaty with India has been under serious consideration since 2006 due to the apprehensions and complaints received against the ‘Mauritian route of round-tripping’ of Indian money through shell companies formed in Mauritius to avoid domestic taxes in India and to route illicit funds.

The amended DTAA between India and Mauritius was signed between the then Indian Finance Minister Arun Jaitley and Minister of Finance and Economic Development of Mauritius Pravind Kumar Jugnauth after prolonged deliberations at the Double Taxation Avoidance Convention (DTAC) held at Port Louis on 10 May 2016. In the first two years starting from 1 April 2017, the capital gains on shares were taxed at 15%, that is, 50% of prevailing capital gains tax rate of 30% in India under the revised treaty. Full rate was made applicable from 1 April 2019 onwards (Press Trust of India, 2016b). The amendment required the companies to have substantial business operations along with employees under their payroll. They should be listed on a registered stock exchange in any of the contracting nations. Moreover, they needed to prove that a total expenditure of INR 2.7 million was made during the immediately preceding 12 months in Mauritius (Kotha, 2018; Press Trust of India, 2016a). R2 observed that ‘interestingly, there was no mention of the other kinds of securities implying that even after 2019, no capital gains tax would be required to be paid for alienation of interest from debt instruments, convertible securities, derivatives and similar financial instruments’.

In 2017, the ‘anti-treaty shopping’ or LoB clause was attributed to trace back the true economic beneficiary of the corporate transactions ‘to confine source-country treaty benefits to entities that are true residents of the treaty partner and are fully taxable in that country’ (Postlewaite & Makarski, 1999; Shukla, 2021). India also implemented the GAAR on 1 April 2017 to trace the dubious transactions by ‘lifting the corporate veil’ and establishing the ‘substance over form’ (PwC, 2017).

Indo–Mauritian capital exchanges post-amendment of the DTAA

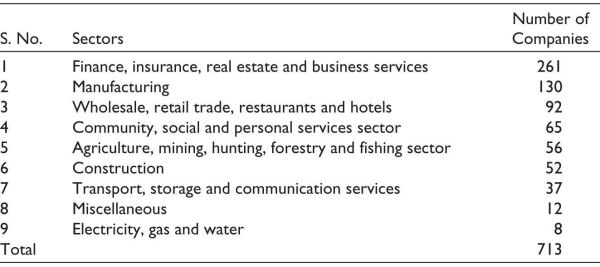

A scrutiny of the Indian investments from July 2007 to June 2023 reveals that out of the nine industrial sectors, the finance, insurance, real estate and business services sector of Mauritius attracted 30% of the Indian investment (not in value terms) followed by the manufacturing sector (15%), as presented in Table 4. However, in reality, not many manufacturing activities are done by the Indian companies in Mauritius. Instead, most of these companies are actually GBCs.

Table 4. Sectoral Distribution of FDI Inflows from India to Mauritius (July 2007-June 2023).

Source: Authors’ compilation from Reserve Bank of India (2023).

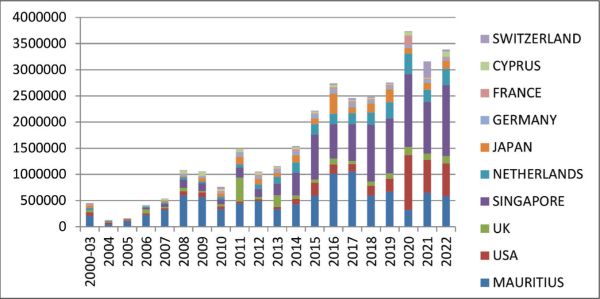

From the Indian perspective, Singapore outpaced Mauritius as the biggest source of foreign capital from 2018 onwards, and later from 2020, USA took the second lead sending Mauritius to the third rank which coincided with the grandfathering of the Indo–Mauritian DTAA (Figure 1). Notably, Singapore also used to extend the same tax benefits as Mauritius prior to the revision of the DTAA with India, and a similar revised DTAA had been signed between India and Singapore with effect from April 2017 itself.

Figure 1. Country-wise and Year-wise FDI Inflows into India.

Source: Authors’ calculation from Reserve Bank of India (2023).

In response to the query as to what according to him is the biggest reason behind this downward slip of Mauritius, R5 commented that

It is not because of the amendment of the DTAA between India and Mauritius that Singapore and the USA has climbed up the ladder as the biggest foreign investors of India. Rather it is because of the grey-listing of Mauritius by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and other such organisations that has pulled Mauritius down in the list of the investing countries in India.

To prevent and monitor global money laundering, proliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons, and terrorism financing the FATF became operational in 1989. Mauritius was grey-listed by the FATF in February 2020 as a non-compliant jurisdiction having strategic deficiencies in countering global money laundering and terrorism financing (Financial Action Task Force, 2023). Subsequently, Mauritius was also EU-Blacklisted as a High-Risk Third Country and entered the UK List of High-Risk Third Countries.

However, Mauritius complied with the FATF demands, and in October 2021 it managed to get out of that list. In January 2022, it was removed from the EU-Blacklist. They were satisfied that there were no longer any strategic deficiencies in the anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) framework (Bowman_Admin, 2022). Presently, Mauritius is only in the ‘Corporate Tax Havens’ list of Oxfam, a non-govt. organisation from Oxford, England, which is a coalition of many humanitarian and development institutions that prioritise poverty alleviation and development assistance (List of the World’s Most Notorious Tax Havens, 2024). Meanwhile, China emerged as a major economic partner of Mauritius by strengthening the trade ties, investing in infrastructural projects and extending grants, and India started receiving more investments from Singapore, its closest ally from South-East Asia, and another tax haven.

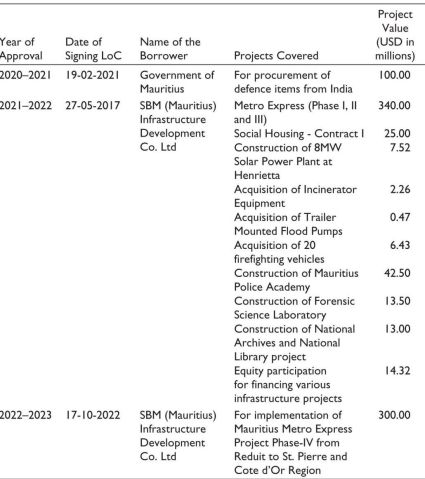

Post-amendment of the DTAA, the Mauritian government approached India to extend line of credit (LoC) and additional investments into their country to boost their economy as well as for the generation of employment, as presented in Table 5 (Press Trust of India, 2016b). Immediately after such an approach, a total amount of credit of USD 465 million was extended by the Government of India to Mauritius on 27 May 2017.

Table 5. Line of Credits (LoC) by India to Mauritius Post-amendment of the DTAA.

Source: India EXIM Bank (2023).

It is worth noting that as of now India has contributed maximum LoC to Mauritius among the entire African region (India EXIM Bank, 2023). Instead of influx of capital in the form of equity, the nature of the mobile capital shifted to the form of loans from the Indian Government itself. State-owned and privately owned Indian companies like RITES, NBCC, HSCC and Larsen and Toubro (L&T) have significant role in building the Mauritian infrastructure. In March 2024, the Prime Minister of India virtually inaugurated an airstrip and a jetty built with support from India at the Agalega Islands in Mauritius, to closely observe and counter-balance China’s expanding influence in the Indian Ocean region (IOR) (Chaudhury, 2024).

Conclusion

International tax havens have always been considered to be a threat to the coveted tax neutrality among the countries contesting for foreign capital investments, and inevitably tax reduction is the most popular way through which the sovereign governments compete for mobile capital (Genschel & Schwarz, 2011). Tax arbitrages strictly depend on cross-border legal regulations and tax rate differentials, leading to increased intensity of tax cooperation among the nations. The capital neutrality principle postulates that lower tax barriers between economies help to determine the location of investments on the basis of economic factors rather than on taxation. However, in reality, due to the paradox of capital neutrality, a country’s desire for neutrality can actually increase the incentives for tax competition for other nations, resulting in an even less efficient use of resources, ceteris paribus. Whatever be the degree of cooperation between the two nations, they have no power to curb down the tax competition existing between them, the Indo–Mauritian case being no different (Chernova, 2022).

Mauritius is one of India’s closest allies due to strong historical links, cultural proximity as well as economic interdependence between them. The Mauritian arguments contend that the variables that contribute to the importance of the Mauritian route were not those stipulated in the treaty but rather those provided by Mauritius itself, including higher labour standards, a workforce, closeness to India, shared history and culture, political stability, protection against expropriation through the law and freedom from restrictions on foreign exchange (Bodell, 1996; Desai & Sanghavi, 2008; Kotha, 2018).

However, of late, there is growing influence of China, India’s major economic contender, in Mauritius. On the one hand, China is becoming the biggest source of trade and investment inflows into Mauritius; on the other hand, replacing Mauritius, Singapore and the USA are becoming the major sources of FDI inflows into India post-amendment of the DTAA in 2016. Apparently, it may seem that such decline in mobility of capital between India and Mauritius is due to the revision of the tax treaties, but the study instead observes that first, the FATF grey-listing of Mauritius, and second, the Chinese economic invasion policy are the real reasons behind such decline in flow of capital between the countries. However, the major limitation of the study is the bias present in the selection of the respondents due to limited responses available for confidentiality reasons.

Tax competition is not only a matter of law, but of ethics and morality as well. No amount of international collaboration can impede tax competition. There are differences in opinion as to whether tax havens are a boon or a bane, a friend or a foe, heavens or hells (Raposo & Mourão, 2013; Stasiunaityte, 2014). However, the intentions of both the investors and the service providers are what matters the most. SIDS and poorer countries tend to cooperate with richer nations in order to maintain capital neutrality which leads to ‘offshorisation of economies’ (Chernova, 2022); surprisingly, high-income economies like the USA, the Netherlands, the UK and Switzerland are also well-recognised tax havens. Tax morale and the inability to customise tax laws to best serve the interests of the country increases the already atrocious expenses of poor governance (Manish & Soni, 2020). Unless human greed is checked, whatever legal modifications are made, the unscrupulous human mind would engineer cunning loopholes out of the legal systems to satisfy its ulterior motives. Grave and worthy punishment might suppress the propensity to evade tax, but that also demands good governance and uncorrupted national systems.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest regarding the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Satabdee Banerjee  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3736-0953

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3736-0953

Verena Tandrayen-Ragoobur  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8977-754X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8977-754X

Ali, A., Agarwal, A., & Dixit, A. K. (2022). Abuse of double taxation avoidance agreement between India and Mauritius. International Journal of Health Sciences (IJHS), 2783–2790. https://doi.org/10.53730/ijhs.v6ns5.9245

Arch Global Consult. (2020, February 19). Authorised Company - Arch Global Consult. Arch Global Consult - Global Business in Mauritius. https://www.archglobalconsult.com/global-business/authorised-company/

Aykut, D., Sanghi, A., & Kosmidou, G. (2017). What to do when foreign direct investment is not direct or foreign: FDI round tripping. World Bank, Washington, DC eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-8046

Bank of Mauritius. (2023). Direct investment flows. https://www.bom.mu/publications-and-statistics/statistics/external-sector-statistics/direct-investment-flows

BBC News. (2021, October 3). Pandora Papers: Your guide to nine years of finance leaks. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-41877932

Bodell, U. B. (1996). Mauritius offers access to India. International Tax Review, 7(3). https://www.proquest.com/openview/7d3ec11eb70ffe7b68538d3c7f4d0ead/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=30282

Bowman, L. W. (2023, August 18). Mauritius | Facts, Geography, & History. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Mauritius

Bowman_Admin. (2022, March 4). Mauritius de-listed—The way forward - Bowmans. Bowmans - Corporate and Commercial Law Firm | Corporate Lawyers | Attorneys. https://bowmanslaw.com/insights/corporate-services/mauritius-de-listed-the-way-forward/#:~:text=The%20repercussions%20of%20Mauritius%20being,which%20adversely%20affected%20the%20economy

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chaudhury, D. R. (2024, February 29). India, Mauritius inaugurate airstrip & jetty in Agalega. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/india-mauritius-inaugurate-airstrip-jetty-in-agalega/articleshow/108117455.cms?from=mdr

Chernova, A. Y. (2022). The paradox of capital neutrality as a reason for the offshorization of economies. Courier of Kutafin Moscow State Law University (MSAL), 8, 148–155. https://doi.org/10.17803/2311-5998.2022.96.8.148-155

Daude, C., Gutierrez, H., & Melguizo, A. (2013). What drives tax morale? A focus on emerging economies. Revista Hacienda Pública Española, 207(4), 9–40. https://doi.org/10.7866/hpe-rpe.13.4.1

Desai, M. A., Foley, C. F., & Hines Jr., J. R. (2005). Do tax havens divert economic activity? Michigan Ross School of Business. http://ssrn.com/abstract=704221

Desai, M. A., Foley, C. F., & Hines, J. R. (2006). The demand for tax haven operations. Journal of Public Economics, 90(3), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2005.04.004

Desai, N., & Sanghavi, D. (2008). The travails of the India Mauritius Tax Treaty & the road ahead. Nishith Desai Associates, 1. https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=iD9nymwAAAAJ&citation_for_view=iD9nymwAAAAJ:8k81kl-MbHgC

Dyreng, S. D., & Lindsey, B. P. (2009). Using financial accounting data to examine the effect of foreign operations located in tax havens and other countries on U.S. multinational firms’ tax rates. Journal of Accounting Research, 47(5), 1283–1316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679x.2009.00346.x

Economic Development Board Mauritius. (2021). Bilateral agreements. https://edbmauritius.org/bilateral-agreements

EDB Mauritius. (2022). Bilateral agreements DTAA. https://edbmauritius.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/DTAA.pdf

Financial Action Task Force. (2023). “Black and grey” lists. Financial Action Task Force (FATF). https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/countries/black-and-grey-lists.html

Genschel, P., & Schwarz, P. (2011). Tax competition: A literature review. Socio-Economic Review, 9(2), 339–370. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwr004

Gunputh, R. P., Jha, A., & Pudaruth, S. (2017). Round tripping and treaty shopping: Controversies in bilateral agreements & remedies forward—The double taxation avoidance agreement (DTAA) between Mauritius and India and the dilemma forward. Kathmandu School of Law Review, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.46985/jms.v5i2.985

India EXIM Bank. (2023). Financial products: Line of credit. https://www.eximbankindia.in/lines-of-credit#

Jaafar, A., & Thornton, J. (2015). Tax havens and effective tax rates: An analysis of private versus public European firms. The International Journal of Accounting, 50(4), 435–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2015.10.005

Jackson, J. K. (2010). The OECD initiative on tax havens. Congressional Research Service. https://info.publicintelligence.net/R40114.pdf

Jalan, A., & Vaidyanathan, R. (2017). Tax havens: Conduits for corporate tax malfeasance. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 25(1), 86–104. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/jfrc-04-2016-0039

Jones, C., & Temouri, Y. (2015). The determinants of tax haven FDI. Journal of World Business, 51(2), 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2015.09.001

Kemme, D. M., Parikh, B., & Steigner, T. (2019). Tax morale and international tax evasion. Journal of World Business, 55(3), 101052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2019.101052

Kotha, A. P. (2018). The Mauritius route: The Indian response. Saint Louis University Journal, 62(1). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3113160

List of the World’s Most Notorious Tax Havens. (2024, January). Worlddata.info. https://www.worlddata.info/tax-havens.php#:~:text=Here%20the%20most%20common%20international,according%20to%20the%20aforementioned%20lists.

Maffini, G. (2009). Tax haven activities and the tax liabilities of multinational groups [Working Papers 0925]. Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation. https://ideas.repec.org/p/btx/wpaper/0925.html

Manish, S., & Soni, A. (2020). Tax havens and money laundering in India. Gujarat National Law University. http://www.igidr.ac.in/conf/money/mfc-11/Manish_Shashank.pdf

Mathur, S., Singhanchi, A., Sam, S. S., & Sharma, A. (2015). India, Singapore and Mauritius: Tax treaty shopping and FDI flows. Asian Journal of Research in Banking and Finance, 5(6), 277. https://doi.org/10.5958/2249-7323.2015.00089.9

Mauritius (Ranked 47th):: Legatum Prosperity Index 2023. (n.d.). Legatum Prosperity Index 2023. https://www.prosperity.com/globe/mauritius

Mauritius: Sub-Saharan Africa. (2023). Sustainable development report. https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/profiles/mauritius/indicators

McCaffery, E. J. (2005). A new understanding of tax. Law & Economics and Legal Studies Research Paper Series. University of Southern California Law School. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/mlr103&div=28&id=&page=

Meade, J. E. (1967). Population explosion, the standard of living and social conflict. The Economic Journal, 77(306), 233. https://doi.org/10.2307/2229302

Mitchell, D. J. B. (2006). The moral case for tax havens. The Liberal Institute of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2010/2392/pdf/24_ OP_pdf.pdf

Molero, J. C., & Pujol, F. (2011). Walking inside the potential tax evader’s mind: Tax morale does matter. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0955-1

Nalsar University of Law Editorial Team. (2023, October 6). Third world approaches to international taxation I: Understanding the history of double taxation avoidance agreements—Centre for tax laws. Nalsar University of Law. https://ctl.nalsar.ac.in/ 2023/10/06/third-world-approaches-to-international-taxation-i-understanding-the-history-of-double-taxation-avoidance-agreements/

Nebus, J. (2019). Will tax reforms alone solve the tax avoidance and tax haven problems? Journal of International Business Policy, 2(3), 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-019-00027-8

Nerré, B. (Ed.). (2001). The concept of tax culture. Annual conference on taxation and minutes of the annual meeting of the National Tax Association (Vol. 94). https://www.jstor.org/stable/41954732

Oakley, S. (2017). The wreck of the ten sail: A true story from Cayman’s past. Polperro Heritage Press.

OCRA Worldwide Mauritius. (2020, August 14). Mauritius. https://www.ocra-mauritius.com/jurisdictions/mauritius/

OECD. (1998). Harmful tax competition. OECD eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1787/ 9789264162945-en

Pickhardt, M., & Prinz, A. (2014). Behavioral dynamics of tax evasion—A survey. Journal of Economic Psychology, 40, 1–19. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167487013001062

Pitkänen, H., & Ronnerstam, L. (2021). Globalization and tax haven countries: A study on the relationship between globalization and the use of tax havens. In Rafael Barros De Rezende, Jönköping International Business School. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1630195/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Postlewaite, P. F., & Makarski, D. S. (1999). The A.L.I. tax treaty study—A critique and a modest proposal. Tax Law, 52, 731–869. https://www.scholars.northwestern.edu/en/publications/the-ali-tax-treaty-study-a-critique-and-a-modest-proposal

Press Trust of India. (2016a, August 13). Government notifies revised tax treaty with Mauritius. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/government-notifies-revised-tax-treaty-with-mauritius/articleshow/53687153.cms?from=mdr

Press Trust of India. (2016b, September 16). Mauritius seeks India’s help, post tax treaty revision. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/mauritius-seeks-indias-help-post-tax-treaty-revision/articleshow/ 54365526.cms

PwC. (2017). GAAR decoded. PwC. https://www.pwc.in/assets/pdfs/publications/2017/gaar-decoded.pdf

PwC. (2024). India-Individual-Foreign tax relief and tax treaties. https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/india/individual/foreign-tax-relief-and-tax-treaties

Raposo, A. L. C. R., & Mourão, P. R. (2013). Tax havens or tax hells? A discussion of the historical roots and present consequences of tax havens. Financial Theory and Practice, 37(3), 311–360. https://doi.org/10.3326/fintp.37.3.4

Reserve Bank of India. (2023). Data on overseas investment. https://rbi.org.in/Scripts/Data_Overseas_Investment.aspx

Rosenzweig, A. H. (2010). Why are there tax havens? William & Mary Law Review, 52(3), 923–996. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A247030766/AONE?u=anon~5eb4547b&sid=googleScholar&xid=adead9b8

Sabnavis, M., & Sawarkar, A. (2016, May 27). Double taxation avoidance agreement (DTAA): Mauritius. Care ratings. https://www.careratings.com/upload/NewsFiles/GlobalUpdates/Double%20Taxation%20Avoidance%20Agreement%20-%20Mauritius.pdf

Shaxson, N. (2011). Treasure islands: Tax havens and the men who stole the world. Random House.

Shukla, G. (2021). Limitation of benefit—The route to curtail tax avoidance or a disguise: An Indian perspective. The Lawyer Quarterly, 11(1), 50–69. https://tlq.ilaw.cas.cz/index.php/tlq/article/view/443

Sooreea-Bheemul, B., & Sooreea, R. (2012). Mauritius as a success story for FDI: What strategy and policy lessons can emerging markets learn? Journal of International Business Research, 11(2), 119. https://scholar.dominican.edu/barowsky-school-of-business-faculty-scholarship/10/

Stasiunaityte, O. (2014). Tax havens—Friends or foes? In P. Raimondos-Møller (Ed.), Copenhagen business school master of science advanced economics and finance (p. 78). https://research-api.cbs.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/58412100/ona_stasiunaityte.pdf

The World Bank. (2020). Doing business 2020: Mauritius. The World Bank. doingbusiness.org. https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/country/m/mauritius/MUS.pdf

Thukral, M. (2022). Treaty shopping: Abuse of double taxation avoidance agreement (DTAA): Special focus on the case study of India’s DTAA with Mauritius and the MLI framework. Dharmashastra National Law University Student Law Journal. https://dnluslj.in/article-treaty-shopping-abuse-of-double-taxation-avoidance-agreement-dtaa-special-focus-on-the-case-study-of-indias-dtaa-with-mauritius-and-the-mli-framework/

Todaro, & Smith, S. (2020). Economic development (13th ed.). Pearson Education.

UNIDO. (2021, February 12). Industrial free zones boost Mauritius’ export-led manufacturing. United Nations Industrial Development Organization. https://www.unido.org/stories/industrial-free-zones-boost-mauritius-export-led-manufacturing

Van’t Riet, M., & Lejour, A. (2018). Optimal tax routing: Network analysis of FDI diversion. International Tax and Public Finance, 25(5), 1321–1371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-018-9491-6

World Happiness, Trust and Social Connections in Times of Crisis | The World Happiness Report. (2023, March 20). https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2023/world-happiness-trust-and-social-connections-in-times-of-crisis/#ranking-of-happiness-2020-2022

Yadav, S. K. (2018). Abuse of double taxation avoidance agreement by treaty shopping in India. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 23(10), 68–73. https://kbng.in/uploaded_files/resources/DTAA_ActJXXO.pdf