1 Stevenson University, Brown School of Business and Leadership, Maryland, USA

2 Business School, University of Nottingham Malaysia, Seminyih, Selangor, Malaysia

3 Jagat Guru Nanak Dev, Punjab State Open University, Patiala, Punjab, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

This article aims to test whether organic food consumers’ perception of organisations’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) matters by examining the specific attributes that consumers prioritise in gauging the corporate CSR of organisations manufacturing organic food products in Malaysia. A structured Likert scale questionnaire was used to collect data from a total of 313 consumers utilising the survey method. Findings suggest that organisations should prioritise stakeholders’ interest through positive health benefits of organic food products, environmental commitment, product knowledge, trustworthy information and affordable prices rather than using CSR as a growth factor to promote quality and sustainability only. The study emphasises the role of the Malaysian government in enhancing the standards of organic food production and processing, which will motivate many companies to venture into organic farming and lead towards less reliance on imports of organic food. This will build up consumer trust and satisfaction towards organic produce. Lastly, there will be an increase in consumer trust and satisfaction towards organic produce as demand increases after the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this study is suitable for organic food manufacturers who intend to improve social image, stakeholder experience and value creation, which will help brand their products. The implications of this study are generalisable not only in Malaysia but worldwide since the world is moving towards the new normal, and precautionary measures to combat health issues are prioritised.

Organic, food products, corporate social responsibility, human values, consumer

Introduction

The demand for organic food products has increased exponentially. It has gained popularity due to consumer perceptions that organic food products are safe, nutritious and healthy. Consuming organic food has been marketed as a healthy alternative and free of chemicals and pesticides (Hidalgo et al., 2022; Zinoubi & Toukari, 2019). Conventionally, consumers tend to consume food that provides them self-fulfilment, regardless of the positive or negative impact on their health. However, of late, more consumers are becoming increasingly concerned about the quality of food products that are safer and healthier (Andrea, 2016; Hossain et al., 2019). It has been observed in one of the developing Asian countries, Thailand, that consumer trust is crucial for food companies to establish market credibility, especially those who manufacture and sell green and organic food (Nuttavuthisit & Thøgersen, 2017). These consumer preference traits have been observed in many Asian developing countries like Malaysia, but there is a substantial literature gap in understanding the changes happening in the organic food market. These literature and industrial gaps are discussed in this article.

According to the IBIS World industry report, consumers have adopted healthy eating options due to health concerns, seeking premium products like organic foods (Hwang & Chung, 2019). This trend is partially driven by concerns arising from modern food production-related techniques, mainly through the overuse of fertilisers and chemicals, which are currently significant causes of health concerns (Gerrard et al., 2013). Past studies have enhanced our understanding of organic food attributes in terms of health, quality, safety and environmental benefits. Consumers are also evaluating other factors, including product price, the producer’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) reputation, the complexity of product information and uncertainty about environmental and social benefits, which will affect their purchase decision (Tong & Su, 2018). The conventional traits of consumers consuming organic food products, including motives, beliefs and attitudes towards organic food products, are also essential to consider (Monier et al., 2009; Zinoubi, 2021). A comparative study was conducted between developed and developing economies, such as France and Morocco, to understand the role of national institutions in the context of organisations’ CSR in the food processing industry. Authors have opined that small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries will use CSR as an economic and marketing tool to promote their organic food products globally (Baz et al., 2016). There is a need for comprehensive research to support the role of the government of developing economies like Malaysia in enhancing companies’ commitment towards sustainability; hence the motivation for this research.

Consumer behaviour studies have shown that consumers’ perception and subsequent behaviour towards certain products is significantly correlated with the CSR of the organisations that produce them. When consumers buy similar products with the same price and quality, the CSR could be the determining factor (Arli et al., 2014). Many researchers provided indicators for CSR assessment that must be grounded in actions concerning social issues that affect companies’ operations. The marketing strategy, termed Marketing 3.0, focuses on increased attention to sustainability by drawing consumers’ attention towards socially responsible organisations (Bonn et al., 2016). Socially responsible companies, therefore, are perceived to demonstrate a solid commitment to human values (Rosario González-Rodríguez et al., 2016). Peloza and Montford (2015) highlighted that consumers consider corporate-level information and food-level attributes while evaluating food products in the firms’ markets. We argue that organisations providing products at affordable prices with reliable information establishing health benefits through environmentally friendly practices may be perceived to be socially responsible. Little research has been done on how consumers perceive organisations to be socially responsible, hence the motivation for this study.

This study examined whether attributes of organic food products, which have been tested and validated in prior studies, such as affordable prices, educating consumers about the product, projecting positive health benefits, knowledge, environmental concern, trust and affordable prices, influence the perception of consumers on the CSR of organisations manufacturing organic food products in Malaysia. The study was guided by the research question:

RQ: Do the attributes influence the perception of consumers on the CSR of organic food manufacturers in Malaysia?

Through a usable sample of 313 survey responses from around Kuala Lumpur (i.e., the capital city of Malaysia), we provide evidence that the factors mentioned above collectively increase consumers’ trust in organic food brands, which, in turn, shapes the intentions of consumers to buy organic products. Our study has several implications, both theoretically and practically.

First, we view CSR initiatives as organisations’ attempts to establish and enhance the legitimacy of their operations and practices. Consumers will only purchase organic food if they trust or possess sufficient confidence that the nature of such foods or aspects relating to their production is genuine, as claimed by organic food manufacturers. Put simply, their likely purchasing behaviour is a ‘reasoned action’ based on how they perceive organic food manufacturers. Many researchers have suggested that the big local organisations, as well as multinational companies, are the major players in CSR implementation in Malaysia, although budget allocations may have differed as per the company’s size, policy and origin of the country (Lu & Castka, 2009).

Practically, the study is suitable for companies intending to improve social image, stakeholder experience and value creation, indirectly aiding in branding their products. Notably, during the COVID-19 and the recovery/post-recovery period, the reliance on organic food products is likely to increase. For example, it was claimed that the demand for organic products ‘doubled’ recently after more Filipinos began buying goods seeking to boost health amid the spread of COVID-19 in the country (Domingo, 2020). The study also provides insights for tightening government policies with respect to CSR and promoting organic food products in Malaysia, especially since there seems to be a lack of awareness among producers, retailers and consumers of the broader extent of organic production and processing standards in local markets (Somasundaram et al., 2016).

This article is organised as follows. The next section details the literature and the theoretical background of this study. This is followed by the formulation of the research model and the introduction of the research methods. Next, we report our findings and discussions. Finally, we conclude this article by outlining its theoretical contributions, practical implications and the future scope of research.

Literature Review

Organic food can be defined as products of farming systems that shun the use of fertilisers and pesticides (Rodriguez-Fernandez, 2016). Typically, organic products contain minimum pollutants from air, soil and water, which is good for the health and productivity of soil, plants, animals and humans (Bonn et al., 2016). Organic farming uses approximately one-third less pesticides than conventional farming at the cost of a potential loss of productivity (Willer et al., 2013), although organic food products need not necessarily be better in taste or quality. However, consumers purchase organic products because they are unique and have superior attributes compared to conventionally grown products (Bellassen et al., 2019; Willer & Lernoud, 2014). Nevertheless, the broader public still relies on conventional products due to their availability, price benefits and perceived quality (Buder et al., 2014; Hossain et al., 2019).

Global Prospect of Organic Food

According to the FiBL-IFOAM survey report (Willer et al., 2013),1 organic farming is practised by 186 countries with ~71.5 million hectares of agricultural land managed by 2.8 million producers. The per capita consumption was €12.8, and the number of countries with organic regulation in 2018 was 87 (Willer et al., 2018). The organic food market is still in its infancy, with Malaysia importing more than 60% of its requirements (Somasundaram et al., 2016). A decade ago, the Malaysian agriculture industry highlighted that ‘Malaysia has the potential to develop and tap into the massive global market for organic produce’ (Gerrard et al., 2013). However, issues concerning accreditations and trust in quality persist (Aziz et al., 2020). Statistics reveal that, unlike in many other developed and developing countries, Malaysia is yet to fully implement standards endorsed as organic by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (Willer & Lernoud , 2019).

One of the efforts of the Malaysian government along these lines includes establishing organic standards in collaboration with five other Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, namely Indonesia, Cambodia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand.2 The standards aim to improve supply chain management while reducing production costs. The Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industries also introduced the Malaysian Organic Certification Scheme (myORGANIC) to recognise farms that practice organic farming based on Malaysian Standard MS 1529:2001, providing guidelines on packaging, processing, labelling and marketing organic food products.3 The 191 farms are spread over 1,848 hectares of land with a total production of 65,591 tonnes, estimated at RM175 million. These statistics indicate the seriousness with which Malaysia is pursuing organic farming and marketing.

CSR and Organic Food

Nguyen et al. (2019) explained the importance of consumers’ CSR perception, which influences their buying intentions. ‘CSR is a management concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns into their business operations and stakeholder interactions’.4 Andrea (2016) explains that the meaning of social responsibility is vast, ranging from being ‘legally and ethically responsible’ to being merely ‘charitable’ or ‘legitimate’. Simone and Hervé (2013) asserted that when firms pursue CSR activities that support the stakeholders’ interest rather than merely using CSR as a growth factor, there can be a market for quality and sustainability. CSR is a dynamic concept that incorporates strategies and specific contextual factors influencing organisational behaviour (Andrea, 2016). CSR is in the interest of businesses and all stakeholders, such as employees, consumers and governments, demand and value the respective efforts (Gerrard et al., 2013). These practices have become popular among governments from various countries with stringent social and environmental regulations (Arli et al., 2014). Thus, the government has a significant role in spearheading CSR practices in their countries. This is particularly important for businesses and institutions dependent on the government’s aspirations and vision concerning social and environmental issues. Researchers claim that CSR is an essential determinant in consumers’ food purchasing (Hartmann et al., 2013). Consumers in developed countries are willing to pay premiums for social and environmental responsibility, as demonstrated by companies selling organic food (Bellassen et al., 2019; Loose & Remaud, 2013), mainly due to its positive impact on creating trust. It is also essential to differentiate CSR messages among consumer groups for firms’ branding strategy (Mueller, 2014).

Therefore, we posit that organic food attributes perceived as necessary by consumers, if considered by companies with reasonable accountability and seriousness, can positively influence consumers’ perception of the organisation’s CSR initiatives and help improve the marketability and branding of the products. Othman et al.’s (2019) research shows that Malaysian companies actively involved in CSR initiatives have experienced increased financial performance and long-term sustainability. This indicates that companies should integrate CSR into their strategic planning to sustain themselves in the market or industries for a long time. These companies believe in disclosing social information and desire to comply with government social policy, thus helping build a corporate image. This can also be a powerful promotional tool as businesses can communicate with their customers about reconstructing society and enhancing positive perception in the eyes of the public (Nasir et al., 2015).

Theoretical Underpinnings

Firms undertake CSR initiatives to enhance the legitimacy of their operations. Suchman (1995) described legitimacy as a generalised perception that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper or appropriate with the norms, values and/or beliefs of the society in which it operates. When society is broken down into its major constituents, the legitimacy theory predicts that firms would place great importance on addressing the concerns of the most influential stakeholder groups (Campbell, 2000). Such an emphasis is highly complementary to that of the stakeholder perspective/theory (Donaldson & Preston, 1995). Devinney et al. (2006) highlighted that companies seeking to benefit from their purported social credentials often score only a pyrrhic victory, as consumers do not always pull their weight in ethical consumption. Put simply, while consumers expect companies to offer products that are produced in a socially responsible manner (Mohr et al., 2001), most do not exhibit a clear preference for products produced by ‘ethical’ companies (Oberseder et al., 2011). For instance, Young et al. (2009) found that 30% of consumers who claim they are very concerned about environmental issues struggle to translate this into purchases. In this context, recent studies found that managers’ motivation to pursue CSR activities sincerely is triggered by organisational drivers and companies’ willingness to change. Organisational drivers are internal factors such as altruism, legitimacy and competitiveness, while drivers of change comprise external factors such as economic responsibilities and profitability. These changes in company policies will lead to businesses’ responsibility towards society for a bright future (Nasir et al., 2015).

Proactive initiatives such as detailed labelling would help consumers concentrate their limited efforts on considering firms’ CSR initiatives, leading to improvements in consumer beliefs, attitudes and intentions (Cicia et al., 2010). However, consumer attitudes and purchase intentions are influenced by CSR initiatives only if the consumers are aware of them (Pomering & Dolnicar, 2009). This study is also informed by the theory of reasoned action (TRA), where consumers’ purchasing behaviour is primarily determined by individual motivational factors, especially behavioural intention and perception. These TRA constructs are empirically excellent predictors of many behaviours (Montano & Kasprzyk, 2008).

The following section of this article scrutinises specific CSR-related attributes of organic products likely to influence consumers’ purchasing behaviour significantly. Each attribute is considered ‘high-fit’, as each is inextricably tied to the nature of organic products. Consumers’ evaluation of CSR initiatives is complex yet structured, during which consumers consider many initiatives (Oberseder et al., 2011). Such an understanding would improve firms’ marketing strategies in the hopes that consumers ‘would stick to their side of the bargain’ when it comes to making actual CSR-informed purchases (Thøgersen et al., 2015).

Health Benefits

Consumers rank health and food safety as the primary quality in determining organic agriculture’s private or personal benefits (Loebnitz & Aschemann-Witzel, 2016). Studies focussed on health benefits as one of the critical attributes of organic food consumption (Curvelo et al., 2019). Health-conscious consumers prefer to remain well-informed about their products and strive to keep healthy by consuming high-quality food (Newson et al., 2015). Thus, health considerations are one of the primary reasons why consumers purchase organic food (Moise et al., 2019). The nutritional value of organic food positively impacted consumers’ attitudes towards organic food, per Liang (2016). However, whether organic food manufacturers can ensure that the organic products they manufacture can provide the perceived health benefits should hypothetically depend upon their commitment to CSR instead of intentions to earn higher profits through premium pricing (Nasir & Karakaya, 2014). Many discussions about organic food products question whether they truly offer the claimed health benefits (Rizzo et al., 2020). We believe that consumers see companies as socially responsible when they can effectively promote and distribute high-quality organic products that offer enhanced health benefits.

H1: Health benefits demonstrated by the company can have a positive influence on consumers’ perception of manufacturers’ CSR.

Knowledge of Organic Products

Informed consumers hold a positive attitude towards organic products because they understand production and processing practices (Hsu et al., 2019). Consumer knowledge is shaped by the information they receive, including labelling, certifications and advertisements. Modern consumers prefer to buy organic products due to the eco-friendly production process and sustainable farming methods. Parameters related to food safety, such as reduced use of chemical fertilisers and minimal usage of artificial preservatives and additives without harming the environment, contribute to a positive attitude among customers towards organic produce (Hidalgo et al., 2022; Rizzo et al., 2020).

Objective knowledge can be acquired through individual preferences (Ajzen et al., 2011), while subjective knowledge pertains to an individual’s perception of their image of a specific topic (Bonn et al., 2016). This influences the attitudes and behaviour of individuals when choosing organic products. In developed countries, knowledge of organic food products has been observed to have both positive and negative effects on consumer choices (Shamsollahi, 2013). We hypothesise that:

H2: Providing more knowledge and awareness of organic products will positively influence the consumers’ perception of manufacturers’ CSR.

Environmental Concerns

Attitude towards consuming organic food is crucial in predicting an individual’s choice of food products (Zinoubi & Toukabri, 2019). Studies on attitudes towards organic food consumption have found influences from external factors such as the environment, trust and cost (Aziz et al., 2020), with environmental concern being a major influence (Rodriguez-Fernandez, 2016). Consumers recognise that organic foods are produced in a way that minimises negative impacts on the environment and can reduce water and soil contamination by avoiding chemical pesticides (Bonn et al., 2016). According to Somasundram et al. (2016), there is a clear connection between consumer concern about the environment and their behaviour towards organic food products. Hence, environmentally aware consumers are likely to make eco-friendly purchases. European customers value green products and are willing to pay for their environmentally friendly features due to their environmental concerns. Research has also shown that environmentally friendly products and processes indicate socially responsible organisations. Enterprises prioritising environmental impacts and taking timely precautions to preserve the environment (Zelazna et al., 2020) are considered socially responsible and can enhance their product branding through word of mouth, which is prevalent in developed countries (Moise et al., 2019). We therefore hypothesise that:

H3: Addressing environmental concerns positively influences the consumers’ perception of manufacturers’ CSR.

Trust in Organic Products

Consumers need to feel secure when purchasing organic products at a premium price, and they seek more information disclosure about these products (Curvelo et al., 2019). Studies have highlighted that distrust of organic food labelling and claims poses a significant barrier to purchasing organic food products (Shamsollahi, 2013). Research also suggests that consumers tend to trust branded organic products with certified labels, indicating that retailers are socially responsible (Rodriguez-Fernandez, 2016). In the case of Egyptian organic products, the absence of state certification through appropriate labels has led to a lack of trust (Willer & Lernoud, 2014). A similar situation exists for Danish organic products, where systematic trust is based on labelling and control schemes supplemented by personal trust (Thorsøe, 2014). Studies have indicated that the perceived value of trust for the success of organic products has not been fully satisfied (Rittenhofer & Povlsen, 2015). Research on online marketing reveals that trust in sponsored links is lower than in organic links unless vendors’ information is reliably disclosed. However, this reduction in trust is not enough to negate the overall effect (Ma et al., 2013).

Various aspects of CSR, including product liability, organic labelling, packaging information and honest labelling of the country of origin, play crucial roles in gaining customer trust and cultivating a stronger pro-social image (Simone & Hervé, 2013). In today’s competitive world, a unique selling proposition (USP) for organic products can be achieved by accurately presenting all the facts, such as sourcing, country details and nutritional facts. These communication strategies contribute to a positive positioning in customers’ minds, fostering loyalty and sustained profitability (Tong & Su, 2018). Zelazna et al. (2020) reported that uncertainty and lack of trust could have a negative impact on consumer perception and attitude. Certified labels are the most essential tool for enhancing corporate transparency. Labels are hybrid instruments because they provide informational features for consumers and economic or marketing incentives for companies. Hence, government policies and regulations are required to enforce and encourage CSR initiatives from businesses, placing importance on labelling (Arli et al., 2014).

H4: Providing trustworthy information about the product positively influences the perception of manufacturers’ CSR.

Price

Price has consistently been one of the most critical factors influencing the purchase of organic products. Previous studies indicate that consumers perceive organic food as more expensive than non-organic alternatives (Simone & Hervé, 2013). While consumers belonging to the middle and upper class generally show optimism towards the premium prices of organic products due to their perceived value (Curvelo et al., 2019; Monier et al., 2009), price remains a significant barrier affecting consumer behaviour towards organics (Guliyeva & Lis, 2020). Research also suggests that individuals face a trade-off between choosing organic food and saving money or buying luxury goods (Zinoubi, 2021). Thus, price is considered a double-edged sword, acting as a barrier while also influencing consumer opinions by associating high prices with high quality (Zelazna et al., 2020). While consumers may be willing to pay a premium for the benefits of organic products, the premium cost still hinders purchase decisions (Sriwaranun et al., 2015). On the contrary, Narine et al. (2015) documented that consumers are willing to pay premium prices for selected organic products based on income levels and per capita income (Muhammad et al., 2015).

Producers and companies are prioritising marketing communications for price-sensitive consumers, highlighting the benefits of organic products compared to traditional farm produce. Efforts have been made to justify higher prices for organic produce by emphasising quality, freshness, food safety, taste and reliable sources. Regional labels have been supported as a solution to control the higher cost of organic products through shorter distribution channels. Therefore, while there are diverse perspectives on the relationship between price and the choice of organic products, we argue that socially responsible organisations are more likely to consider the cost–benefit for consumers, especially when targeting the middle-income group.

H5: Affordable price positively influences the consumers’ perception of the manufacturers’ CSR.

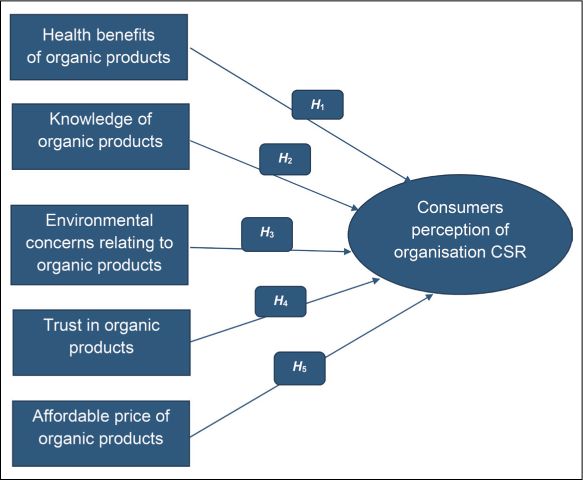

The abovementioned hypotheses have led to the development of the theoretical framework depicted in Figure 1. As this is a foundational study, we avoid exploring interrelationships among variables; instead, we focus on testing the direct linear relationships between the independent and dependent variables.

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework.

Note: CSR: Corporate social responsibility.

Research Framework and Methodology

Data Collection and Sample

Data were collected using a questionnaire adapted from a previous study. Table 1 provides details of past studies upon which the questionnaire was based. The six variables were derived from various studies (Table 1).

Using a purposive sampling technique, self-administered questionnaires were distributed at supermarkets and minimarkets in the Klang Valley, including a screening question to identify consumers who purchase organic food products. Purposive sampling is a non-probability technique where participants are selected based on researchers’ judgement to ensure they can provide valuable inputs to achieve the study objectives. Since participants needed to be users of organic food products and willing to complete the survey in supermarkets and minimarkets, purposive sampling was deemed the most appropriate approach. A total of 370 questionnaires were distributed, resulting in a response rate of 84%, and 313 questionnaires were deemed usable.

Respondents’ Profile

The respondents were diverse in gender, age, education level, occupation, income and family size. The demographic details are presented in Table 1. The survey included 156 females (49.8%) and 157 males (50.2%), ensuring an unbiased gender representation. In terms of age, 43.8% of respondents were in the 20–29 age category, 26.2% in the 30–39 category, 17.2% in the 40–49 category and the remaining in the ‘more than 50 years’ category. Employment-wise, 58.8% were employed, 19.5% were self-employed, 13.1% were homemakers and 8.6% were either waiting for a job or students undergoing internship training. Educational qualifications varied, with 56.5% holding a degree, 7% having a diploma, 29.8% having postgraduate qualifications and the rest being professionals. Regarding family size, 65% had 4–6 members. Regarding monthly income, 63.1% fell between MYR 2,500 and MYR 12,000, with almost equal numbers above MYR 12,000 and below MYR 2,500.

Initial Analysis

The questionnaire, comprising 35 items, was divided into six factors derived from past literature and perception studies. The factors included health benefits, knowledge, environmental concerns, trust, price and CSR. Each factor, except CSR, had six items, while CSR had five (refer to Table 2). The reliability of the factors was confirmed by Cronbach’s alpha, with all factors scoring above 0.7, indicating suitability for further analysis. Skewness and kurtosis tests were within permissible limits. The Kaise–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure (0.833) indicated that the overall data were suitable for further testing. Observing Table 2, the mean scores were highest for price, followed by health benefits and environment, while trust and knowledge had relatively lower mean scores.

Correlation Analysis

Table 3 presents the correlation statistics, revealing that four out of the five attributes were correlated at the 1% significance level. Only the correlation involving price was observed at the 5% significance level.

Cronbach’s alpha is a coefficient of consistency that assesses the internal consistency or reliability of a set of variables measuring a single dimension. A Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.7 is generally recommended for better reliability in measurement (Hair et al., 1998; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1995).

Multiple Regression

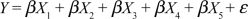

Multiple regression analysis is employed to investigate the association and establish a predictor equation between the consumer perception of organisation CSR (dependent variable) and a store’s health benefits, knowledge, environment, trust, price and product attributes (independent variables). As a result, three hypotheses need to be tested, and the statistical equation corresponding to this model is formulated for further analysis:

Findings

The following regression equation was developed based on the theoretical studies.

Discussion

The figures in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 reveal that all the hypotheses are supported. It can be observed that consumers’ perception of the manufacturer’s CSR is positively influenced by (a) detailing essential health benefits of consuming organic food, (b) building trust in the information provided, (c) environmental concerns tacked by manufacturers and (d) providing adequate knowledge of the products that they market. It is surprising that the price of the product, although significant, is not the most essential criterion set by consumers. This implies that consumers do not perceive premium prices for organic products as an indicator of compromised CSR. However, consumers do not place higher importance to price when judging organisational CSR.

We hypothesised that health benefits demonstrated by the company can positively influence consumers’ perception of manufacturers’ CSR. This implied that organisations indicating the health benefits of their products transparently are likely to gain higher visibility and are perceived to portray a better CSR. Our research finding supports this hypothesis, which is also the highest contributor (β = 0.458). Socially responsible manufacturers will indicate the real health benefits of their products, as iterated by Nasir and Karakaya (2014). However, many manufacturers hype the health benefits of organic food products to charge a premium price (Rizzo et al., 2020). Consumers also look for good returns as ‘value for money’ is a critical parameter after purchasing premium-priced organic and green food (Johnston, 2008). Our study emphasises that the appropriate health benefits can influence consumers’ perception of CSR, which will influence the consumers’ buying intention. Our studies thereby support some of the recent findings in this area.

Next, we hypothesised that the perception of manufacturer CSR is influenced by the information disseminated by the manufacturers (knowledge). This was supported, although compared to other variables, knowledge had a lower coefficient (β = 0.266) despite the fact that the price was the lowest. The implication is that consumers prioritise the knowledge they gain about the product through the information provided in the product. Researchers determined that the social responsibility of organic food importers includes labelling, certification and codes of conduct (George, 2015). Consumers will emphasise proper labelling regarding calorie content and other health benefits (Johnston, 2008). While these are important for imported goods, they are also crucial for farmed products and manufacturers, which has not been studied. This study closed that gap. This is a concern in Malaysia, since the knowledge and awareness among Malaysian producers, retailers and consumers are lacking (Somasundaram et al., 2016). While our study supports many past studies, we contrasted the opinion of (Hassan et al., 2015), who claim that Malaysians are not too keen on the knowledge of organic food products.

Third, we hypothesise that environmental concerns impact consumers’ perception of manufacturers’ CSR. Our research supports this hypothesis, which is currently a global issue and not merely regional. Global environmental concerns include climatic conditions, land procurement and green labels (Guliyeva & Lis, 2020). Land issues and environmental attitudes are the key concerns in the growth of the Malaysian organic sector (Haris et al., 2018). Johnston (2008) suggested that modern-era consumers are well-educated and aware of global issues around organic and green food products, such as environmental impact and health benefits. They have shown ethical behaviour by choosing the right product at the right price from the right place; consumers spend their time selecting ethical companies in the food industry. While the concerns are highlighted, how they impact the consumers’ perception of manufacturers’ CSR remains underexplored. Our research conveys a clear message that consumers prioritise environmental concerns in gauging the manufacturers’ CSR. This could likely influence the branding of the locally manufactured products, which justifies why Malaysian consumers prefer imported organic products to locally manufactured ones (Somasundaram et al., 2016). The findings are also consistent with past studies, which show that environmental concerns are crucial in influencing consumers’ choice of organic products (Nasir & Karakaya, 2014). This is not surprising as organic food production is often regarded as low risk in terms of water or ground pollution. Such environmental considerations are also the characteristic of socially responsible organisations. Manufacturers of organic products must, therefore, demonstrate the use of environmentally friendly processes.

We also hypothesise that trust in the products will impact consumers’ perception of manufacturers’ CSR. The second-highest coefficient supported this compared to knowledge (β = 0.381). Security when using any product, specifically food or skin-related, is essential for humans to remain healthy. One of the key CSR activities of any organisation is to develop trust in the consumers. This is true for organic food consumers (Nguyen et al., 2019). Moreover, some authors opined that small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries will use CSR as an economic and marketing tool to promote their organic food products in the global space (Baz et al., 2016). Researchers also claim that a lack of trust in control systems and the authenticity of the fool sold can negatively impact consumers’ buying intentions (Nuttavuthist & Thogersen, 2017). In China, trust in food manufacturers was vital in establishing overall trust in organic food products (Ayyub et al., 2018). It has been observed in Thailand, a developing country, that consumer trust is the critical factor for food companies to establish market credibility, especially those who manufacture and sell green and organic food (Nuttavuthisit & Thøgersen, 2017). We have yet to establish the manufacturers’ trust through transparent information in Malaysia. Our findings make it apparent that effective dissemination of detailed information on (a) the nature of organic food and its health benefits and (b) how organic food firms address environmental concerns positively influences consumer perception of organisational CSR. Furthermore, their perception is also shaped by their trust in the information provided.

Finally, the touted benefits of organic products would positively influence the attitude of consumers, which would induce them to pay a premium. Premium price is a matter of concern for many Malaysians (Somasundaram et al., 2016). Furthermore, Peloza et al. (2015) highlighted that consumers use corporate-level information and food-level attributes as essential factors to consider while evaluating food products marketed by the firms. Therefore, we posit that socially responsible organisations would aim to provide quality at affordable prices instead of overly focusing on profit maximisation. Indeed, we found affordable pricing to be a significant factor. However, Malaysian consumers give the least priority to the price of products, indicating that Malaysians do understand that organic food products will warrant higher prices compared to non-organic food products, which they might be willing to pay. However, manufacturers who claim very high premiums with profit intentions and without demonstrating value additions will have trouble branding through CSR.

Conclusion and Implications

The primary aim of this study is to investigate whether specific attributes influence the CSR perception of manufacturers producing organic food products. Through multiple regression analysis, it is noteworthy that all five attributes studied significantly relate to how consumers perceive the CSR of organic food manufacturers.

First, the findings indicate that increasing consumers’ knowledge, awareness of health benefits and trust in organic food products influence their intentions to buy such products and shapes their perception of the manufacturer’s CSR. Second, when consumers perceive that the manufacturer is environmentally conscious, they are more likely to have a positive view of an eco-friendly manufacturer. Third, despite being price-conscious, consumers are willing to pay a premium for organic food products, contributing to a positive perception of the manufacturer’s CSR. These findings align with the idea that consumers’ purchasing actions are reasonable, involving a careful evaluation of organisational CSR.

The practical implications of this study are twofold. First, it is crucial for manufacturers seeking to enhance their social image, stakeholder experience and value creation—essential elements for branding and rebranding their products. Despite price increases, more consumers are expected to turn towards organic products during the COVID-19 pandemic, provided they are convinced of the legitimacy of these products. Second, CSR initiatives aim to establish and enhance the legitimacy of organisational operations and practices. Consumers will only purchase organic food if they trust that the nature of the food or the production process is genuine, as the manufacturers claim.

Few studies have explored the relationship between organic product attributes and the perception of organisational CSR. As a developing nation aspiring to make its mark in international markets, Malaysia holds vast potential for manufacturing and marketing organic food products. Therefore, the study’s third practical implication underscores the need for highly informative labels on organic foods. Encouraging adherence to standards set by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements and obtaining endorsements and certifications from relevant authorities can enhance the perceived reliability and trustworthiness of information. Additionally, organic food firms must be responsive to consumers’ concerns and contribute to social welfare, aligning with the increasing consumer interest in health and well-being.

Lastly, the study’s results can be extended to other major cities in Malaysia, such as Penang, Putrajaya and Ipoh, providing insights into how consumer behaviour varies across different regions compared to Kuala Lumpur, the capital. The study also serves as a valuable reference for future research in different countries. Based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia’s capital and one of Asia’s known economic hubs, the findings provide insights into the operations of many international companies and the city’s cosmopolitan nature. Multinational companies can use these insights to undertake CSR-related initiatives, contributing to the sustainability of the organisation and the marketability of their products globally.

Limitations and Future Research

This study acknowledges certain limitations. Convenience sampling may restrict the generalisability of the findings, and future researchers are encouraged to employ a broader and more representative probability sample. The limited sample size, particularly from Kuala Lumpur, poses a challenge in generalising the study’s outcomes. Additionally, the inclusion of in-depth qualitative analysis methods and diverse stakeholder perspectives could have further enriched the research findings. While the empirical findings contribute valuable insights into organic food products and manufacturers’ CSR, future studies should aim for a more extensive and regionally diverse sample covering all regions in Malaysia. Exploring different methodologies could allow a deeper understanding of the interrelationships between independent variables or the potential interaction effects of dummy variables such as gender and income levels. Qualitative methods can be employed to delve more profoundly into consumers’ perceptions and manufacturers’ perspectives on the organic food market. This multifaceted approach would enhance the comprehensiveness and depth of future research in this domain.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Tamana Anand  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3826-9833

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3826-9833

Notes

Ajzen, I., Joyce, N. M., Sheikh, S., & Cote, N. G. (2011). Knowledge and the prediction of behavior: The role of information accuracy in the theory of planned behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 33(2), 101–117.

Andrea, M. K. (2016). Buying organic—decision-making heuristic and empirical evidence from Germany. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(7), 552–561.

Arli, D., Bucic, T., Harris, J., & Lasmono, H. (2014). Perceptions of corporate social responsibility among Indonesian college students. Journal of Asia Pacific Business, 15(3), 231–259.

Ayyub, S., Wang, X., Asif, M., & Ayyub, R. M. (2018). Antecedents of trust in organic foods: The mediating role of food-related personality traits. Sustainability, 10(10), 3597.

Aziz, M. F. B. A., Mispan, M. S. B., & Doni, F. (2020). Organic food policy and regulation in Malaysia: Development and challenges. In B. C. GOH & R. Price (Eds), Regulatory issues in organic food safety in the Asia Pacific (pp. 151–170). Springer.

Baz, J. E., Laguir, I., Marais, M., & Stagliano, R. (2016). Influence of national institutions on the corporate social responsibility practices of small- and medium-sized enterprises in the food-processing industry; differences between France and Morocco. Journal of Business Ethics, 134, 117–133.

Bellassen, V., Martin, E., & Villaverde, L. (2019). Organic farming in the vicinity of conventional arable crops: Which impact on revenues and costs? International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 15(3), 195–208.

Bonn, M. A., Cronin, J. J., & Cho, M. (2016). Do environmentally sustainable practices of organic wine suppliers affect consumers’ behavioral intentions? The moderating role of trust. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 57(1), 21–37.

Buder, F., Feldmann, C., & Hamm, U. (2014). Why regular buyers of organic food still buy many conventional products—product-specific purchase barriers for organic food consumers. British Food Journal, 116(3), 390–404.

Campbell, D. J. (2000). Legitimacy theory or managerial reality construction? Corporate social disclosure in Marks and Spencer Plc corporate reports, 1969–1997. Accounting Forum, 24(1), 80–100.

Cicia, G., Cembalo, L., & Giudice, T. D. (2010). Consumer preferences and customer satisfaction analysis: A new method proposal. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 17(1), 79–90.

Curvelo, I. C. G., de Morais Watanabe, E. A., & Alfinito, S. (2019). Purchase intention of organic food under the influence of attributes, consumer trust and perceived value. Revista de Gestão, 26(3), 198–211.

Devinney, T. M., Auger, P., Eckhardt, G., & Birtchnell, T. (2006). The other CSR: Consumer social responsibility. In Leeds University Business School research papers series [Research Paper No. 15-04]. Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Domingo, K. (2020, 10 March). Demand for organic products doubles as COVID-19 cases rise in PH. https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/03/10/20/virgin-coconut-oil-organic-healthy-food-coronavirus-covid-19-manila

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91.

George, A. (2015). Social responsibility and import of certified organic food: A case study of 13 Swedish firms. Södertörn University. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:900101/FULLTEXT02

Gerrard, C., Jenssen, M., Smith, L., Hamm, U., & Padel, S. (2013). UK consumers reactions to organic certification logos. British Food Journal, 5, 727–742.

Guliyeva, A. E., & Lis, M. (2020). Sustainability management of organic food organizations: A case study of Azerbaijan. Sustainability, 12(12), 5057.

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Haris, M., Garrod, N. B., Gkartzios, G., & Amy, M. P. (2018). The decision to adopt organic practices in Malaysia: A mix-method approach. Agricultural Economics Society—AES, 92nd Annual Conference, April 16–18, 2018, Warwick University, Coventry, UK. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.273485

Hartmann, M., Heinen, S., Melis, S., & Simons, J. (2013). Consumers’ awareness of CSR in German pork industry. British Food Journal, 115(1), 124–141.

Hassan, S. H., Yee, L. W., & Ray, K. J. (2015). Purchasing intention towards organic food among generation Y in Malaysia. Journal of Agribusiness Marketing, 7, 16–32.

Hidalgo, G., Monticelli, J. M., Pedroso, J., Verschoore, J. R., & de Matos, C. A. (2022). The influence of formal institution agents on coopetition in the organic food industry. Journal of Agricultural & Food Industrial Organization, 20(2), 61–74.

Hossain, M. T. B., Rahman, M. A., & Techato, K. (2019). Consumer buying behaviour and social responsibility in respect of organic foods: Cross-cultural evidence. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 15(2), 145–164.

Hsu, S. Y., Chang, C. C., & Lin, T. T. (2019). Triple bottom line model and food safety in organic food and conventional food in affecting perceived value and purchase intentions. British Food Journal, 121(2), 333–346.

Hwang, J., & Chung, J. E. (2019). What drives consumers to certain retailers for organic food purchase: The role of fit for consumers’ retail store preference. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47, 293–306.

Johnston, J. (2008). The citizen–consumer hybrid: Ideological tensions and the case of whole foods market. Theory and Society, 37, 229–270.

Liang, R. (2016). Predicting intentions to purchase organic food: The moderating effects of organic food prices. British Food Journal, 118(1), 183–199.

Loebnitz, N., & Aschemann-Witzel, J. (2016). Communicating organic food quality in China: Consumer perceptions of organic products and the effect of environmental value priming. Food Quality and Preference, 50, 102–108.

Loose, S. M., & Remaud, H. (2013). Impact of corporate social responsibility claims on consumer food choice: A cross-cultural comparison. British Food Journal, 115(1), 142–166.

Lu, J. Y., & Castka, P. (2009). Corporate social responsibility in Malaysia—experts views and perspectives. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16(3), 146–154.

Ma, Z., Liu, X., & Hossain, T. (2013). Effect of sponsored search on consumer trust and choice. International Journal of Electronic Business Management, 11(4), 227–237.

Mohr, L. A., Webb, D. J., & Harris, K. E. (2001). Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behaviour. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 35(1), 45–72.

Moise, M. S., Gil-Saura, I., Šeric, M., & Molina, M. E. R. (2019). Influence of environmental practices on brand equity, satisfaction and word of mouth. Journal of Brand Management, 26(6), 646–657.

Monier, S., Daniel, H., Véronique, N., & Simioni, M. (2009). Organic food consumption patterns. Journal of Agricultural & Food Industrial Organization, 7(2), 1–25.

Montano, D. E., & Kasprzyk, D. (2008). Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral mode. In K. Glanz (Ed.), Health behavior: Theory, research and practice (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Mueller, T. S. (2014). Consumer perception of CSR: Modelling psychological motivators. Corporate Reputation Review, 17, 195–205.

Muhammad, S., Rahman, E. F., & Ullah, R. U. T. (2015). Factors affecting consumers’ willingness to pay for certified organic products in United Arab Emirates. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 46(1), 37–45.

Narine, L. K., Ganpat, W., & Seepersad, G. (2015). Demand for organic produce: Trinidadian consumers’ willingness to pay for organic tomatoes. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 5(1), 76–91.

Nasir, N. E. M., Halim, N. A. A, Sallem, N. R. M., Jasni, N. S., & Aziz, N. F. (2015). Corporate social responsibility: An overview from Malaysia. Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences, 4(10), 82–87.

Nasir, V. A., & Karakaya, F. (2014). Consumer segments in organic foods market. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31(4), 263–277.

Newson, R. S., Van, D. M., Beijersbergen, A., Carlson, L., & Rosenbloom, C. (2015). International consumer insights into the desires and barriers of diners in choosing healthy restaurant meals. Food Quality and Preference, 43, 63–70.

Nguyen, P. M., Vo, N. D., & Nguyen, N. P. Y. S. (2019). Corporate social responsibilities of food processing companies in Vietnam from consumer perspective. Sustainability, 12(1), 71.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). The assessment of reliability. Psychometric Theory, 3, 248–292.

Nuttavuthisit, K., & Thøgersen, J. (2017). The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: The case of organic food. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(2), 323–337.

Oberseder, M., Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Gruber, V. (2011). Why don’t consumers care about CSR? A qualitative study exploring the role of CSR in consumption decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(4), 449–460.

Othman, N., Latip, R. A., & Ariffin, M. H. (2019). Motivations for sustaining urban farming participation. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 15(1), 45–56.

Peloza, J., Ye, C., & Montford, W. J. (2015). When companies do good, are their products good for you? How corporate social responsibility creates a health halo. Policy & Marketing, 34, 19–31.

Pomering, A., & Dolnicar, S. (2009). Assessing the prerequisite of successful CSR implementation: Are consumers aware of CSR initiatives? Journal of Business Ethics, 85(2), 285–301.

Rittenhofer, I., & Povlsen, K. K. (2015). Organics, trust, and credibility: A management and media research perspective. Ecology and Society, 20(1), 6.

Rizzo, G., Borrello, M., Dara Guccione, G., Schifani, G., & Cembalo, L. (2020). Organic food consumption: The relevance of the health attribute. Sustainability, 12(2), 595.

Rodriguez-Fernandez, M. (2016). Social responsibility and financial performance: The role of good corporate governance. Business Research Quarterly, 19(2), 137–151.

Rosario González-Rodríguez, M., Carmen Díaz Fernández, M., & Simonetti, B. (2016). Corporate social responsibility perception versus human values: A structural equation modelling approach. Journal of Applied Statistics, 43(13), 2396–2415. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2016.1163528

Shamsollahi, A. (2013). Factors influencing on purchasing behaviour of organic foods [Master’s thesis]. Multimedia University.

Simone, M. L., & Hervé, R. (2013). Impact of corporate social responsibility claims on consumer food choice: A cross-cultural comparison. British Food Journal, 115(1), 142–166.

Somasundram, C., Razali, Z., & Santhirasegaram, V. (2016). A review on organic food production in Malaysia. Horticulturae, 2(3), 12.

Sriwaranun, Y., Gan, C., Lee, M., & Cohen, D. A. (2015). Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic products in Thailand. International Journal of Social Economics, 42(5), 480–510.

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610.

Thøgersen, J., Barcellos, M. D., Perin, M. G., & Zhou, Y. (2015). Consumer buying motives and attitudes towards organic food in two emerging markets: China and Brazil. International Marketing Review, 32(3/4), 389–413.

Thorsoe, M. H. (2014). Credibility of organics—knowledge, values and trust in Danish organic food networks [Doctoral dissertation]. Department of Agroecology—Agricultural Systems and Sustainability Aarhus University.

Tong, X., & Su, J. (2018). Exploring young consumers’ trust and purchase intention of organic cotton apparel. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 35(5), 522–532.

Willer, H., Lernoud, J., & Kilcher, L. (2013). The world of organic agriculture. Statistics and emerging trends 2013. FiBL and IFOAM.

Willer, H., Lernoud, J., & Kilcher, L. (2018). The world of organic agriculture statistics and emerging trends 2018: Summary. https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/34674/1/willer-etal-2018-world-of-organic-summary.pdf

Willer, H., & Lernoud, J. (2014). The world of organic agriculture: Statistics and emerging trends (p. 304). Research Institute of Organic Agriculture.

Willer, H., & Lernoud, J. (2019). The world of organic agriculture statistics and emerging trends 2019. https://ciaorganico.net/documypublic/486_2020-organic-world-2019.pdf

Young, W., Hwang, K., McDonald, S., & Oates, C. J. (2010). Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustainable Development, 18(1), 20–31.

Zelazna, A., Bojar, M., & Bojar, E. (2020). Corporate social responsibility towards the environment in Lublin Region, Poland: A comparative study of 2009 and 2019. Sustainability, 12(11), 44–63.

Zinoubi, Z. G. (2021). Effects of organic food perceived values on consumers’ attitude and behavior in developing country: Moderating role of price sensitivity. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Science, 58(3), 779.

Zinoubi, Z. G., &. Toukabri, M. (2019). The antecedents of the consumer purchase intention: Sensitivity to price and involvement in organic product: Moderating role of product regional identity. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 90, 175–179.