1 Department of Business Administration, East West University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Corporate governance receives considerable attention from various stakeholders due to the search for potential agents that cause threats to sound corporate management practices. The fall of Enron and Arthur Anderson was an eye opener toward the journey of long years of corporate scandals and corruption. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which includes various codes and guidelines, evolved as an immediate solution to the problem. Traditionally, accounting has become an integral part of managing corporate governance as it is central to generating financial information for various stakeholders. However, research attention, so far, centers around public accountants due to their universal legitimacy in performing public account attestation services. Management accountants can also play important roles in strengthening corporate governance by instilling sound management accounting practices in various corporate affairs where governance is under threat. This dimension is grossly ignored in the existing literature, narrowing the role of accounting in a broader spectrum of governance. Applying the integrative literature review method as an epistemological paradigm, this study undertakes a theoretical attempt to highlight the roles that management accountants can play in strengthening the governance of firms from both external and internal perspectives. The incremental contribution of the article is to enlarge the remit of corporate governance by aligning the functionalities of management accountants with the mainstream study of corporate governance. It opens further research agendas for academics, practitioners, regulators, and other stakeholders.

Corporate governance, management accounting practices, integrative literature review, management accounting practice gaps

Introduction

There is no strong reference regarding the genesis of governance and its absorbance in the business spectrum. Since the development of a corporate form of business, a potential conflict between owners and managers has been observed, from which corporate governance (CG) evolves (Wells, 2010). The concept of separating ownership from control is further extended by Berle and Means (1932) by considering large US organizations, which eventually becomes a solid foundation for CG. The US economy witnessed a consistent boom after World War II, with a surprising growth in its leading corporations. The governance (internal) of companies was grossly missing during this period of prosperity (Cheffins, 2009). During this era, “managed corporations” were the US economic vanguard, where managers took the leadership and directors and owners followed.

The attention given to analyzing the state of CG during the 1970s and 1980s was exclusively directed toward US corporations (Denis & McConnell, 2003). However, there had been a radical change in the pattern, style, and coverage of research on CG globally by 2003 (Denis & McConnell, 2003). This is due to the demonstration of high-level corporate scandals and corruption that have been exposed, leading to a big question on the inherent governance mechanism. Prevention, very importantly, receives the highest attention, which may be addressed through the enforcement of various management control mechanisms. CG has received considerable attention as an antidote to corruption.

No formal definition directly addresses the principles of good governance. Rather, these principles have been identified and discussed by researchers, different committees, and practitioners, considering the underlying context. It will be a serious challenge to accommodate all relevant aspects systematically archived in the literature. Existing governance frameworks are reportedly inadequate because they consider governance from only a compliance perspective (Seal, 2006). In the context of this “ticking the box” culture, accounting research has concentrated primarily on how CG impacts financial accounting (Al Lawati et al., 2021). This perspective limits the scope of such research to external CG mechanisms, ignoring the alignment and integration of external requirements with internal organizational processes (Ratnatunga & Alam, 2011). As the management accountant perspective has rarely been considered in CG research (Ratnatunga & Alam, 2011), our study fills this gap. This study takes the following research questions:

What roles do management accountants play in strengthening corporate governance? How does management accounting practice impact corporate governance beliefs in firms?

This study deploys an integrative literature review method to generate thematic materials in support of the research questions. The principal debate on which the article develops its research theme is that external auditors remain at the center, acting as mediators of agency problems in the CG mechanism. As a proxy measure of CG, regulators always rely on accuracy in financial reporting. However, the interplay of internal and external mechanisms may strengthen the CG thinking of firms, whereby management accounting takes entry into the scene. This study argues that CG receives a complete structure when management accounting practices are implemented properly to address the requirements of major stakeholders. The remaining part of the study is structured as follows: the second section presents a literature review, which is followed by the research method in the third section. The fourth section covers the analysis and findings of the study. Finally, the article concludes in the fifth section.

Literature Review

Research in CG has received wider attention during the past two decades and covers a wide array of disciplines, including business, sociology, and economics (Aguilera et al., 2015). Researchers have brought a few relevant literature to identify gaps in the current study. Accounting has long been utilized as a tool to attain ideal CG (Seal, 2006). The recent moves in regulatory changes confirm the added importance of accounting information for CG purposes (e.g., Basel Committee, 2010). In a study by Olojede and Erin (2021), the relationship between CG mechanisms and creative accounting practices has been investigated in Nigeria to understand the impact of the Financial Reporting Council of Nigeria (FRCN) Act. The study investigates the role of the FRCN Act in improving CG mechanisms while reducing creative accounting practices. Rather than protecting the rights and interests of a particular group of stakeholders (say, shareholders), quality accounting information should target all stakeholders. Otherwise, it will develop an unbalanced impact, leading to the deterioration of the governance system (Zou, 2019). To instill and improve a sound governance structure, there is no alternative other than specific and quality accounting information (Tang, 2015).

Most of the literature on CG addresses the quality of accounting information, chartered accountants’ roles, general accounting, etc. Several studies address the nexus between financial accounting information and CG, including the contribution of financial accounting information in promoting the governance of corporations (Bushman & Smith, 2001) and in providing required information for implementing governance mechanisms (Sloan, 2001). Nevertheless, few studies (Christine et al., 2011) have addressed the efficacy of management accounting systems in establishing CG mechanisms. Studies (e.g., Indjejikian & Matejka, 2006) also find that management accounting systems, in effect, serve two principal purposes, namely, improving controls and enhancing decision-making. Other studies also confirm that management accounting generates the required information to plan and control activities in an organization (Siti et al., 2011). In another study, Honggowati et al. (2017) look for any impact of CG on the extent of strategic management accounting disclosure in organizations and find that different CG parameters have different patterns of impact on the strategic management accounting disclosure level.

Various management accounting practices used in organizations have implications, either to a smaller or greater extent, in CG (Seal, 2006). It is important to confirm that necessary reporting and monitoring activities are accommodated internally in organizations without limiting the role of auditors and relevant regulators as external monitors (Seal, 2006). To ensure internal governance, importance is given to management accountants who are certified and, at the same time, whose activities are guided by a defined ethical code. It never relies on simply a heterogeneous body of management accounting tools and techniques (Seal, 2006). To be specific, management accountants possess the ability to apply the CG narrative to withstand the potential threat to their profession that may be caused by the manipulation of their understanding and knowledge of management accounting tools and techniques. Concerning this proposition, this study argues that accounting practices help to develop the culture of governance thinking in firms. As there is a dearth of studies addressing these issues in existing literature, this study considers it a potential research gap and conducts an archival analysis to guide further research in this area.

Research Methodology

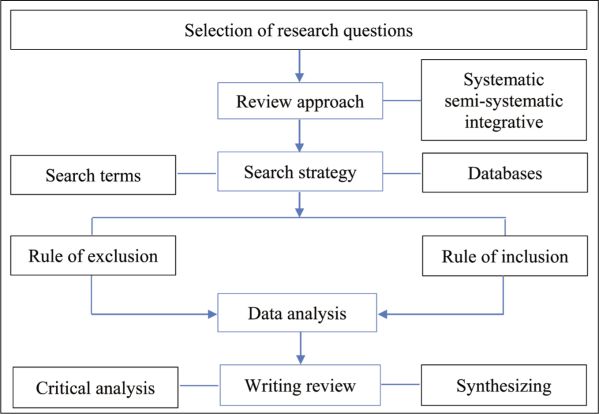

This study uses the literature review method to answer the research questions. The literature review method is one of the best methodological tools to find answers to various research questions (Snyder, 2019). This study develops a solid foundation to advance the knowledge of CG and its connection with management accounting by confirming findings and perspectives from various published works. To emerge something beyond the replication of previous results, a high-quality literature review needs to uncover mysteries in choosing relevant articles to gather data and additional insights (Palmatier et al., 2018). Through this method, our special focus is on (a) discussing relevant literature in selected areas, (b) identifying gaps in existing research, and (c) creating new research agendas. To assess, analyze, and synthesize the relevant literature on CG and management accounting practices, we used integrative reviews to build new theoretical frameworks and perspectives (Torraco, 2016). It aims to critically review and re-conceptualize existing knowledge so that an extension of the theoretical basis of the selected topic can be undertaken for further exploration (Snyder, 2019). To ensure the rigor and quality of an integrative review, Whittemore and Knafl (2005) prescribed a five-step method: (a) identifying the problem, (b) searching the relevant literature, (c) evaluating the captured data, (d) analyzing the selected data, and (5) presenting the findings. Similarly, our integrative review follows the steps depicted in Figure 1.

We begin by selecting a few research questions, followed by choosing the review approach. Later, it is important to finalize a search strategy to fetch the relevant literature (Snyder, 2019). A search strategy encompasses the selection of search items, relevant databases, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. We have identified four search terms: accounting, management accounting, CG, and corruption. We have selected six academic databases—Elsevier, Emerald, JSTOR, Springer, Wiley, and Taylor & Francis—for selecting relevant articles. However, it becomes difficult for us to locate appropriate articles that will help us to proceed with our research questions. Two reviewers have been recruited to help us with the process. We have then chosen the rules for inclusion, considering only specific journals within a timeframe. It also fails to serve our purpose, ending with a very faulty sample while limiting our selection to some specific journals, periods, or even search terms. We may also miss studies that contradict other studies or would have been more relevant to our case (Snyder, 2019). We have finally selected the Google Scholar database and used the selected search terms to identify relevant works for our study.

Figure 1. Literature Review Method.

To confirm the validity and reliability of the search protocol, we have utilized the expertise of two reviewers. Since the search results yield many materials, reviewers are advised to read the abstract of each paper before selecting the article for a thorough review. Later, the researchers sit down with the reviewers to carry out the review step by step: (a) reading the abstracts first for the initial selection and (b) reading the full text of selected articles later to confirm the final selection (Snyder, 2019). To identify other potentially relevant articles, the researchers also checked the references of selected articles as an additional strategy.

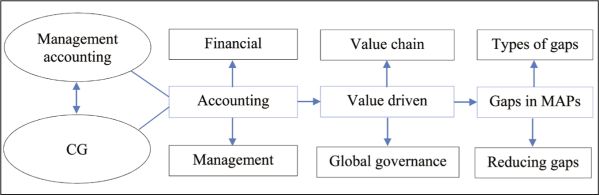

Once the final sample is selected, the important phase of the literature review begins with the deployment of a specific technique to conduct an analysis. An integrative review doesn’t follow any standard for data analysis (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). It may follow a descriptive pattern for presenting information and may sometimes present a central idea or theoretical perspective for general understanding. The final structure of a review article is based on the selected approach, which dictates the kinds of information required and the level of detail. While writing the review, we integrate historical analysis within the field (e.g., Carlborg et al., 2014); select potential areas to conduct further research (e.g., McColl-Kennedy et al., 2017); develop theoretical models, themes, or categories (e.g., Snyder et al., 2016; Witell et al., 2016); and provide evidence relating to an effect (e.g., Verlegh & Steenkamp, 1999). We have developed a conceptual framework (Figure 2) to support us in writing an integrative review in the next section.

Figure 2. Conceptual Framework of the Study.

Analysis and Findings

The integrative literature review reveals a few key themes that guide this section. The thesis presented here is based on the existing records, which serve two purposes: first, it presents the existing state of the interplay between CG and management accounting practices, and second, it directs areas for further exploration. The whole section is segregated into four sub-sections: (a) CG, (b) accounting and CG, (c) management accountants and value chain, and (d) prevalent management accounting practice gaps to improve the governance thinking of firms.

Corporate Governance: Mechanisms, Theories, and Framework

A governance structure integrates various business policies, control mechanisms, and guidelines, driving the business toward achieving its objectives while satisfying the needs of the stakeholders (Mrabure & Abhulimhen-Iyoha, 2020). Investors prefer to invest in well-managed companies due to the presence of the CG mechanism (Mehmood et al., 2019). A strong CG mechanism helps to connect the management with the shareholders (Sehrawat et al., 2019). In a nutshell, the separation of ownership and control requires good governance and involves various mechanisms to ensure good governance (Farooq et al., 2022).

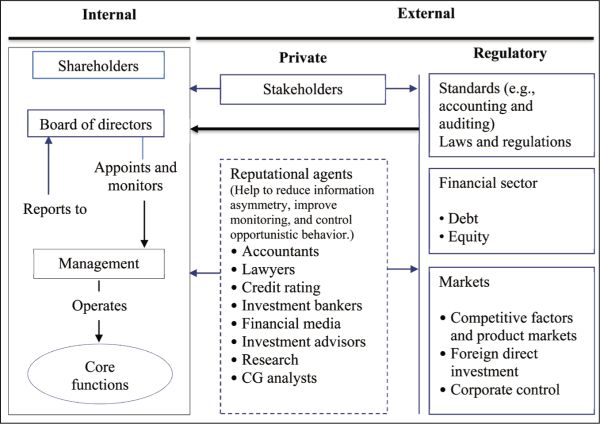

The governance mechanism (Figure 3) is divided into internal and external categories (Raithatha & Haldar, 2021). Internal mechanisms include variables characterizing a board structure, including board duality, the proportion of independent directors, debt–equity ratios, and qualifying shareholdings of executive directors (Kapil & Mishra, 2019). Internal mechanisms generate the principal sets of controls for a corporation, which monitors the progress and activities and takes corrective measures if required. They maintain the large internal control fabric while serving the internal objectives of the corporation and its internal stakeholders. These objectives include, among others, managing operations smoothly, defining reporting lines clearly, and implementing systems of performance measurement.

Figure 3. Governance Mechanisms of Modern Corporations.

External control mechanisms are developed to serve the interests of entities that are external to organizations, such as governments, regulatory agencies, trade associations, different pressure groups, etc. External parties usually initiate the mechanism to impose external requirements on organizations in terms of policies, guidelines, regulations, and advice (Tian et al., 2015). It is the desire of external stakeholders that organizations at least voluntarily report the status and compliance of external governance mechanisms if it is not required mandatorily.

These external and internal mechanisms delve into a few fundamental theories of CG, that is, shareholders theory (Friedman, 1970), stewardship theory (Davis et al., 1997), upper echelons theory (Hambrick & Mason, 1984), and stakeholders’ theory (Freeman, 1984). The shareholder theory states that management is responsible for maximizing the value for shareholders who act as agents of the shareholders to operate the business on their behalf, and thus, they have the moral and legal obligation to entertain the interests of the shareholders (Murphy & Smolarski, 2020). The stewardship theory presumes that managers take on the role of stewards, and they are motivated to work in the best interest of their owners. However, organizational performance largely depends on the characteristics of the top-level management, which is captured in another theory of CG, the upper echelons theory (Hambrick & Mason, 1984). In stakeholders’ theory, on the other hand, managers enjoy a wider scope of coverage whereby all groups are included, not only the shareholders, whose actions or activities can affect the business (Cordeiro & Tewari, 2015). Aggregately, internal and external mechanisms generate a CG framework to reflect an interplay between internal motivations and external challenges governing the behavior and performance of firms.

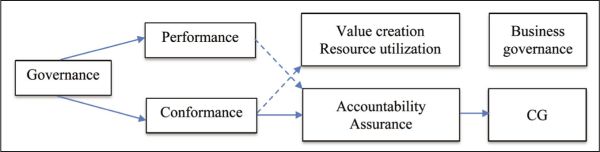

In this study, our particular attention goes to the roles of management accountants and management accounting practices in strengthening CG thinking in firms. Our principal referral on the CG framework that connects management accountants and management accounting practices is prescribed by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) (2009). This framework is composed of the performance and conformance dimensions (Ratnatunga & Alam, 2011) representing the entire value generation, utilization of resources, and applied accountability framework of an organization (Williams & Seaman, 2014). The performance dimension focuses on various opportunities and inherent risks, business strategies, value generation, and utilization of resources, which guide the formal decision-making process in an organization. The conformance dimension, on the other hand, includes various compliance requirements in connection with laws and regulations, CG codes, accountability, transparency, and the confirmation of assurances to stakeholders.

Through the governance framework, IFAC explicitly considers both CG and business governance under a broader governance spectrum. Though there exists some form of reciprocity between conformance and performance, they also have a clear demarcation line to set their scope. Management accountants’ role in the performance dimension is crucial in value creation and resource utilization (Ojra et al., 2021). Business governance is essentially practiced in firms through different management accounting techniques addressing the resource utilization motive, whereby maximum value addition for the stakeholders is targeted. On the other hand, the financial accounting stream takes care of CG through accountability and selling assurance as a form of conformance to established norms, rules, and regulations. Through this framework (Figure 4), IFAC opens the scope of management accounting into the CG realm.

Figure 4. IFAC-Proposed Governance Framework.

Source: Adapted from IFAC (2009).

Accounting and Corporate Governance

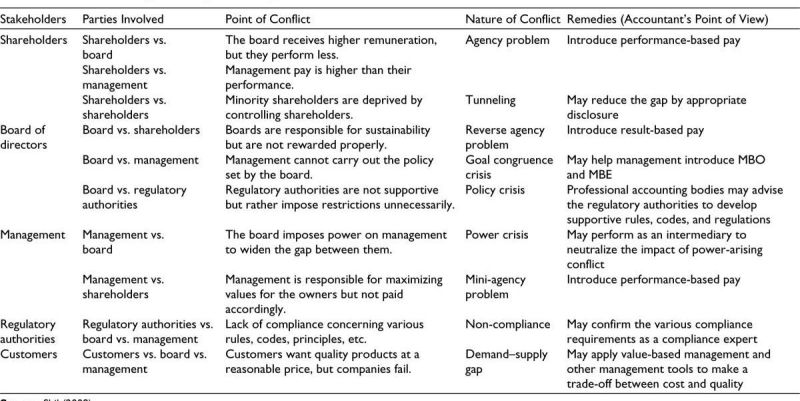

There is a dramatic change in the demand to raise the baseline compliance requirements in the field of CG practices due to serious dissatisfaction among the stakeholders (Prasad & James, 2018). A gradual shift from soft law has been observed as a response to the concerns. The newly enacted SOX Act 2002 and the revised listing rules in the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ have uplifted mandatory requirements for financial disclosure, nominations in various committees and boards, and audit policies. Different Asian countries also introduce much stricter compliance requirements as a follow-up response. In a study, Shil (2008) summarized the events where conflicts may arise among different stakeholder groups, causing threats to the governance system. The study also prescribes mechanisms whereby accountants play important roles in resolving problems and restoring the governance system, as presented in Table 1. Some generic problems mentioned in the study are agency problems, tunneling, power (ego) crises, non-compliance, policy crises, etc. Various stakeholders are involved in corporate management, and these problems are very common to develop, causing chaos where accountants can perform as mitigators under the code of CG.

Table 1. Role of Accounting in Ensuring Good Corporate Governance.

Source: Shil (2008).

Agency problems result when personal interests receive added priority over common interests and individuals compromise with corporate goals to entertain their own goals (Guinote, 2017). When the stockholding pattern results in concentration, leaving a large number of stocks with few majority stockholders, tunneling may arise to oppress the minority shareholders who have no voice in the decision-making process (Solarino & Boyd, 2020). As compliance experts, accountants are familiar with different regulatory and other requirements and maintain proper checklists to save the company from any sort of non-compliance issues. Power crisis, on the other hand, is demonstrated at the top-level management due to the divergences in choosing the preferred course of action (Mangin et al., 2021). Accountants, through their rules and routines, can effectively handle and intervene in various issues to resolve them and accelerate the governance thinking in organizations.

Financial Accounting and Corporate Governance

CG received worldwide attention for the massive collapses of big corporate giants such as Enron, WorldCom, and others during the first decade of this century (Dibra, 2016). These failures raise a legible question about the ability of existing rules and regulations, which have collectively failed to protect the interests of stakeholders. Researchers and academicians began fresh research, and regulatory authorities developed various codes and guidelines for immediate application. As a result, the whole world witnessed the passage and implementation of various prescriptions, for example, Sarbanes Oxley in the United States, the Cadbury Report in the United Kingdom, the Dey Report in Canada, the Vienot Report in France, the King’s Report in South Africa, the Olivencia Report in Spain, the Cromme Code in Germany, and Principles and Guidelines on CG in New Zealand. In most cases, these guidelines, codes, or legal provisions aim to improve the corporate ecosystem relating to CG (Basu & Dimitrov, 2010).

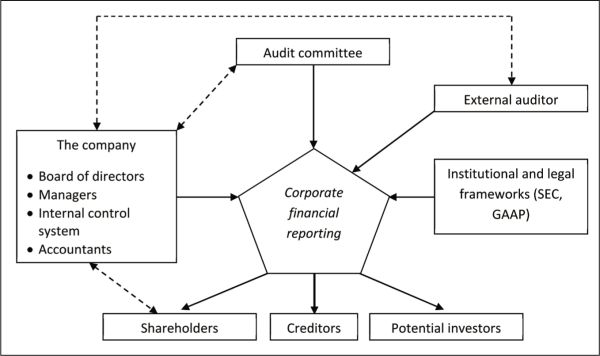

Good CG aims to develop a corporate structure to ensure transparency and accountability for various stakeholder groups. Different stakeholders (Figure 5) are connected in a CG mechanism that develops an internal structure. CG mechanisms are mostly embedded in financial reporting systems in every country (D.png) nescu et al., 2021). Based on this financial reporting system, a code of CG is designed in different countries. In return, CG takes care of the quality of the financial reporting system (Cohen et al., 2004).

nescu et al., 2021). Based on this financial reporting system, a code of CG is designed in different countries. In return, CG takes care of the quality of the financial reporting system (Cohen et al., 2004).

Figure 5. The Financial Reporting System.

The CG mechanism and financial reporting system are intertwined. There is a high degree of overlap between various stakeholders and the purposes of these stakeholders in both the CG and financial reporting systems. The financial reporting system presents a company before external parties and produces a clear picture of the performance of the company (D.png) nescu et al., 2021). Financial information generated from the formal financial reporting system is the first and foremost authenticated source of information about the performance of management for external parties (Sloan, 2001). The board of directors, together with the management, prepares and validates a set of financial statements to report to the respective parties to discharge their responsibilities. Such statements will go through the attestation process by independent auditors. The auditors are employed by the owners with the duty to carry out independent review and scrutiny to come up with an expert opinion regarding the true and fair view of the accompanied financial statements (DeFond & Zhang, 2014). Thus, they play a very important role in confirming CG through their activities.

nescu et al., 2021). Financial information generated from the formal financial reporting system is the first and foremost authenticated source of information about the performance of management for external parties (Sloan, 2001). The board of directors, together with the management, prepares and validates a set of financial statements to report to the respective parties to discharge their responsibilities. Such statements will go through the attestation process by independent auditors. The auditors are employed by the owners with the duty to carry out independent review and scrutiny to come up with an expert opinion regarding the true and fair view of the accompanied financial statements (DeFond & Zhang, 2014). Thus, they play a very important role in confirming CG through their activities.

Management Accounting and Corporate Governance

Management accounting has traditionally been intended for internal use in organizations. However, due to its ability to generate value and provide current and forward-looking information to management, it becomes an effective tool for ensuring CG (Williams & Seaman, 2010). To ensure good governance, it is a presumption that appropriate internal reporting and monitoring mechanisms are in place in addition to the support extended by external monitors such as auditors and regulators. However, making a clear distinction between financial and managerial accounting is challenging, though such a distinction holds an academic and pedagogical role (Ma et al., 2022). So far, management accounting has not received due attention in strengthening CG practices. In some instances, management accounting has been connected with CG, mentioning the contribution of different management accounting tools and techniques to facilitate governance initiatives in organizations (Mayanja & Van der Poll, 2011). The board of directors immensely benefited from using management accounting in formulating and controlling various business strategies (Salemans and Budding, 2023). Some management accounting tools used to formulate business strategies include the PESTEL framework, SWOT analysis, Porter’s Five Forces model, etc.

Management control systems in organizations are also supported by management accounting reports where critical success factors are duly identified to draw the attention of decision-makers who are involved in implementing control measures as a part of broader performance management goals (Leitner & Wall, 2015). These reports provide every direction regarding the variances between actual performance and targeted performance, which enable the board to take corrective measures. A wide array of management accounting tools is extensively used while approving important financial decisions, appraising the performance of the CEO and BOD, supporting and counseling the CEO, and finally complying with CG requirements (Arif et al., 2023; Mayanja & Van der Poll, 2011).

Some of the items in financial statements received extra attention due to their ability to manipulate the information. Management accountants can play a strong role in validating those accounts as they take care of the internal control system (Ala-Heikkilä & Järvenpää, 2023). In this way, management accounting can ensure CG in financial reporting, too (Ascani et al., 2021). Based on our integrative review, we emphasized two major areas of management accounting that are found to be connected with CG. First, we cover the connection between the value chain and governance, where management accounting causes value maximization to drive organizations to generate value for owners (Merici et al., 2020). Second, we refer to various gaps that exist in management accounting practices that may be reduced further to strengthen CG practices in organizations (Shil et al., 2014).

Value Chain and Governance

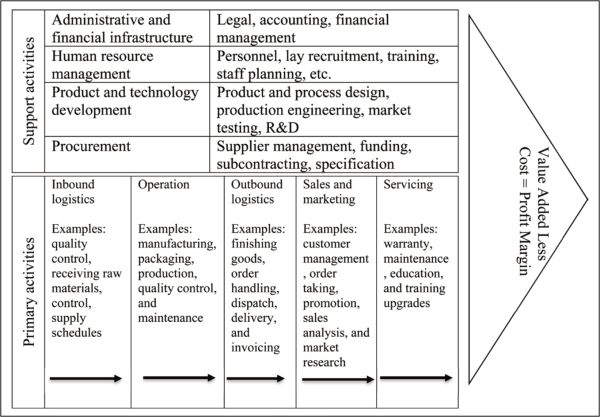

Porter (1985) advocated the first value chain analysis, which was further extended by Shank (1989) and Shank and Govindarajan (1992) in the accounting literature. The sole purpose of value chain analysis is to identify, analyze, connect, and utilize various activities in the value chain and capitalize on the benefits of their synergies (Abbeele et al., 2009). The central idea of the analysis is to break up “the chain of activities that runs from basic raw materials to end-use customers into strategically relevant segments to understand the behavior of costs and the sources of differentiation” (Shank & Govindarajan, 1992). To utilize Porter’s (1985) value chain analysis in management accounting, Shank and Govindarajan (1992) introduced a value chain costing method covering the costing dimension. This technique essentially considers the firm as an external element, linking it with different dimensions of value-added activities in the chain associated with the provision of products or services. To accelerate productivity via the value chain and to continue with the competitive advantage resulting from it, governance acts as an important instrument.

The core focus of CG is to ensure values for its wider stakeholder groups (Bui & Krajcsák, 2024). Management accounting practices are designed such that they can plan, monitor, and control the value-added activities of firms through implementing the value chain (Qiu et al., 2023). Business is a combination of various activities. These activities fall into either of two categories: primary or secondary. Altogether, there are nine generic activities (Figure 6). Out of these nine activities, five fall under primary activities serving the main purpose of the business, extending its scope of activities from sourcing raw materials to after-sales services. The remaining four activities ensure the required support needed to proceed with the primary activities smoothly. These support activities in the value chain facilitate all the primary activities in four selected areas where management accountants dominate the organizational rules and routines (Dahal, 2018). Successful management of the business value chain through all these nine activities provides management accountants an opportunity to take care of the broader interests of the business in generating the required profit/margin.

Figure 6. Value Chain.

Source: Adapted from Dahal (2018).

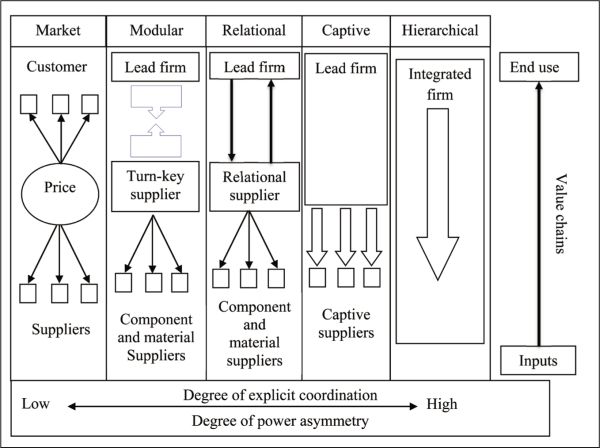

There are different types of governance systems, and it is necessary to select the appropriate type relevant to the value chain (Gereffi et al., 2005). The connections between activities within a chain develop a range of value chains extending from the market characterized by arm’s-length relationships to hierarchical value chains having direct ownership of production processes (Abbasi & Varga, 2022). There are three more network-styled patterns of governance within these two categories (Figure 7), that is, modular, relational, and captive (Gereffi et al., 2005; Strange & Humphrey, 2019). In modular value chains, suppliers respond to the requirements of customers while producing products and require a large volume of customized information flow. However, the lead firm emphasizes the development, penetration, and protection of markets for end products (Sturgeon, 2002). In the relational form of the value chain, buyers and sellers negotiate, developing mutual dependence between them. It also permits leading firms and suppliers to respond to any emerging issues to resolve any conflicts using norms of reciprocity (Sturgeon, 2002). In captive networks, larger buyers take the market lead, and small suppliers depend on them transactionally (Gereffi et al., 2005).

Figure 7. Typology of Governance Systems in Value Chains.

Source: Gereffi et al. (2005).

Thus, value chain analysis, in its generic and extended forms, becomes an important area where management accountants and management accounting practices enhance CG. The latest developments in the field of strategic management accounting (e.g., activity-based costing and management, balanced scorecard, lean production, management, etc.) categorically prioritize value-based management, where management accountants are involved in protecting business interests (Nuhu et al., 2023). However, there exist some relational gaps at varied levels that restrict management accountants from performing to the satisfaction of stakeholders, and these gaps act as strong barriers to achieving governance (Shil et al., 2014). The next section explains the gaps in detail.

Management Accounting Practice Gaps and CG

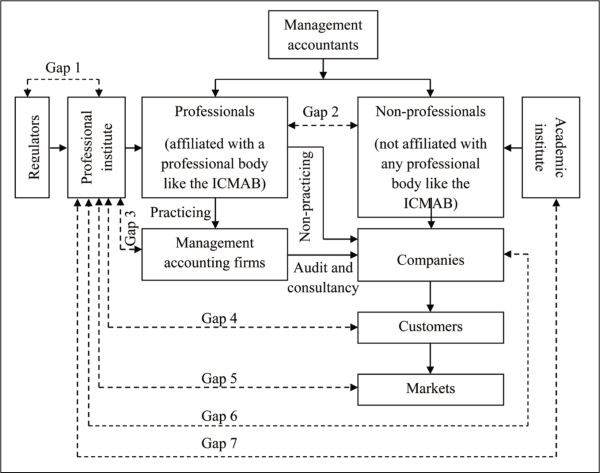

The choice of different management accounting tools in different firms is very specific to the requirements of that firm, which are contingent upon different factors (Ojra et al., 2021). It has been witnessed that firms apply a compromised method of implementing management accounting techniques to strike a balance between practitioners’ judgment and owner-managers expectations (Abed et al., 2022). This compromise limits the potential of management accountants to perform to their fullest capacity (Trevisan & Mouritsen, 2023). Shil et al. (2014) conducted a study to highlight this situation, resulting in a few gaps (Figure 8) in management accounting practices that eventually affect the governance culture of firms.

Figure 8. Gaps in Management Accounting Practices.

Source: Shil et al. (2014).

The analysis results in a total of seven gaps and nine agents. These seven gaps act as critical bottlenecks that develop compromising attitudes among the management accountants, and eventually management accounting practices fail to diffuse at the desired level. Similarly, all these nine agents form broader stakeholder groups that are very loosely connected. The further the connections are among the agents, the lesser the diffusion of management accounting practices becomes (Wolf et al., 2020). To strengthen management accountants’ role in ensuring governance, it is very important to tighten the connection among the stakeholders. Shil et al. (2014) claim that when the stakeholders make a responsible move to come close to each other, shortening the boundaries of roles and responsibilities, there will be a visible improvement in governance thinking. All seven gaps have been summarized here, and such gaps exist in every economy to a different extent depending on the context of the economy.

The liaison gap (Gap 1) represents the weak effort exerted by the professional institute with the local and international regulators to instill favorable treatment. The status gap (Gap 2) exists among practitioners. Such gaps arise from positional dispersion, which develops complexities in role profiles due to perceptions of the possession of knowledge, required skill, authority-responsibility status, connectivity with power, etc. A compliance gap (Gap 3) arises when practitioners fail to comply with various legal and regulatory requirements due to a lack of knowledge and understanding. In Bangladesh, we have some certified management accounting firms that provide cost audits, management consultancy, and other accounting and finance-related services. However, the institutes are struggling to ensure a wide variety of activities for registered firms to choose from. It has been successful in getting some regulatory directives to conduct cost audits and other certifications, against which it develops some record rules and guidelines and provides training to develop the required skillsets among the practitioners.

The satisfaction gap (Gap 4) results from a very loose connection between professional institutes and customers, whereby the institute fails to understand the requirements of customers. Management accounting practices mostly serve the interests of customers (Nair & Nian, 2017); however, there is no formal reciprocity between them in the existing setup. The institute may take the initiative to inform the customers regarding “citizens’ rights” and mutually develop some understanding with the consumer association. It will accelerate the process of governance thinking among the largest group of stakeholders in the market who are currently left aside in the whole governance process. The authoritative gap (Gap 5) results from the absence of formal recognition of the profession by the market. The accounting profession works to achieve broader public interest, and thus, it requires approval from them as well. Regulatory support, trust, and belief in professionals, involvement of professionals in social processes, and power of approval are certain parameters that signify the absence of such a gap in any market. The profession needs to consider value addition for everybody; it goes against governance if one party receives preference at the expense of another party. In Bangladesh, it is observed that the rights of employers are protected, putting less priority on the rights of others, for example, customers (Shil et al., 2014).

The surveillance gap (Gap 6) is found in the relationship between the institute and companies. The institute certifies management accountants who work for different companies. However, there exists a very loose connection between them. This loose connection is reflected in job advertisements, eligibility requirements, job descriptions, etc. The knowledge gap (Gap 7) exists between professional institutes and academic institutes. Both professional and academic institutes play a strong role in ensuring sound practices through the reciprocity of knowledge. Addressing all these gaps will bring the CG agents closer to positioning management accountants in a central role.

Conclusions

This article aims to present management accountants’ roles and management accounting practices to strengthen CG by applying an integrative literature review approach. Public accountants, in effect, are involved in ensuring CG as they are in the process of attestation services. Historically, they have tried to reduce agency problems by connecting the goals of both principals and agents. However, this article argues that management accounting also serves an important role in ensuring governance via internal mechanisms (Nur et al., 2019).

IFAC (2009) prescribes a governance framework covering both corporate and business governance, thereby enlarging the scope of governance. CG is a process of conformance to different rules and regulations, while business governance requires efficient utilization of resources to achieve targeted performance. Management accounting practices, in effect, are aligned with this function. This article argues that the management accountant’s job addresses resource utilization and value generation for owners and other stakeholders, which is the core focus of CG. The incremental contribution of this work is embedding the functionalities of management accountants with the conformance of CG from an internal perspective. In particular, value chain analysis and gaps in management accounting practices are discussed to open a new area of CG for further exploration.

The generic version of the value chain analysis as proposed by Porter (1985) has received considerable attention within strategic management accounting in the form of value chain costing. It takes proper care of customer value addition and resource utilization. Based on an integrative literature review, this article presents researchable arguments supporting the role of management accountants and management accounting practices in rebuilding CG in firms. It also refers to the gaps in management accounting practices as an obstacle to positioning management accounting as a tool for CG. However, the major limitation of the article is that it applies the literature review method to develop a further understanding of CG. Further studies may be initiated by applying various quantitative and qualitative research methods to confirm the arguments of this study. A couple of papers have addressed the role of management accounting in CG (Seal, 2006; Mayanja & Van der Poll, 2011); however, this article brings an extension to that by considering gaps in management accounting practices.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Nikhil Chandra Shil  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5540-801X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5540-801X

Abbasi, M., & Varga, L. (2022). Steering supply chains from a complex systems perspective. European Journal of Management Studies, 27(1), 5–38.

Abbeele, A. D., Roodhooft, F., & Warlop, L. (2009). The effect of cost information on buyer-supplier negotiations in different power settings. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(2), 245–266.

Abed, I. A., Hussin, N., Ali, M. A., Haddad, H., Shehadeh, M., & Hasan, E. F. (2022). Creative accounting determinants and financial reporting quality: Systematic literature review. Risks, 10(4), 76.

Aguilera, R. V., Desender, K., Bednar, M. K., & Lee, J. H. (2015). Connecting the dots: Bringing external corporate governance into the corporate governance puzzle. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 483–573.

Ala-Heikkilä, V., & Järvenpää, M. (2023). Management accountants’ image, role and identity: Employer branding and identity conflict. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 20(3), 337–371.

Al Lawati, H., Hussainey, K., & Sagitova, R. (2021). Disclosure quality vis-à-vis disclosure quantity: Does audit committee matter in Omani financial institutions? Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 57(2), 557–594.

Arif, H. M., Mustapha, M. Z., & Jalil, A. A. (2023). Do powerful CEOs matter for earnings quality? Evidence from Bangladesh. PLoS ONE, 18(1), e0276935.

Ascani, I., Ciccola, R., & Chiucchi, M. S. (2021). A structured literature review about the role of management accountants in sustainability accounting and reporting. Sustainability, 13(4), 2357.

Basel Committee. (2010). Basel Committee Principles for Enhancing Corporate Governance. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision.

Basu, N., & Dimitrov, O. (2010). Sarbanes-Oxley, governance, performance, and valuation. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 18(1), 32–45.

Berle, A. A., & Means, G. C. (1932). The Modern Corporation and Private Property. Macmillan.

Bui, H., & Krajcsák, Z. (2024). The impacts of corporate governance on firms’ performance: From theories and approaches to empirical findings. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 32(1), 18–46.

Bushman, R. M., & Smith, A. J. (2001). Financial accounting information and corporate governance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32(1–3), 237–333.

Carlborg, P., Kindström, D., & Kowalkowski, C. (2014). The evolution of service innovation research: A critical review and synthesis. Service Industries Journal, 34(5), 373–398.

Cheffins, B. R. (2009). Did corporate governance “Fail” during the 2008 stock market meltdown? The case of the S&P 500. Business Lawyer, 65(1), 1–65.

Christine, D., Birgit, F. D., & Christine, M. (2011). Corporate governance and management accounting in family firms: Does generation matter? International Journal of Business Research, 11(1), 24–36.

Cohen, J., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. (2004). The corporate governance mosaic and financial reporting quality. Journal of Accounting Literature, 23(1), 87–152.

Cordeiro, J. J., & Tewari, M. (2015). Firm characteristics, industry context, and investor reactions to environmental CSR: A stakeholder theory approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(4), 833–849.

Dahal, R. K. (2018). Management accounting and control system. NCC Journal, 3(1), 153–166.

D.png) nescu, T., Sp

nescu, T., Sp.png) t

t.png) cean, I.-O., Popa, M.-A., & Sîrbu, C.-G. (2021). The impact of corporate governance mechanism over financial performance: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability, 13(19), 10494.

cean, I.-O., Popa, M.-A., & Sîrbu, C.-G. (2021). The impact of corporate governance mechanism over financial performance: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability, 13(19), 10494.

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20–47.

DeFond, M., & Zhang, J. (2014) A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2–3), 275–326.

Denis, D. K., & McConnell, J. J. (2003). International corporate governance. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 38(1), 1–36.

Dibra, R. (2016) Corporate governance failure: The case of Enron and Parmalat. European Scientific Journal, 12(16), 283–290.

Farooq, M., Noor, A., & Ali, S. (2022). Corporate governance and firm performance: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Corporate Governance, 22(1), 42–66.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, September 13, 1970, 122–126.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104.

Guinote, A. (2017). How power affects people: Activating, wanting, and goal seeking. Annual Review of Psychology, 68(1), 353–381.

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206.

Honggowati, S., Rahmawati, R., Aryani, Y. A., & Probohudono, A. N. (2017). Corporate governance and strategic management accounting disclosure. Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management, 1(1), 23–30.

Indjejikian, R. J., & Matejka, M. (2006). Organizational slack in decentralized firms: The role of business unit controllers. Accounting Review, 81(4), 849–872.

International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). (2009). International Good Practice Guidance, Evaluating and Improving Governance in Organizations. IFAC.

Kapil, S., & Mishra, R. (2019). Corporate governance and firm performance in emerging markets: Evidence from India. Theoretical Economics Letters, 9(6), 2033–2069.

Leitner, S., & Wall, F. (2015). Simulation-based research in management accounting and control: An illustrative overview. Journal of Management Control, 26(2), 105–129.

Ma, L., Chen, X., Zhou, J., & Aldieri, L. (2022). Strategic management accounting in small and medium-sized enterprises in emerging countries and markets: A case study from China. Economies, 10(4), 74.

Mangin, T., André, N., Benraiss, A., Pageaux, B., & Audiffren, M. (2021). No ego-depletion effect without a good control task. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 57, 102033.

Mayanja, M. K., & Van der Poll, H. M. (2011). Management accounting: An instrument for implementing effective corporate governance. African Journal of Business Management, 5(30), 12050–12065.

McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Snyder, H., Elg, M., Witell, L., Helkkula, A., Hogan, S. J., & Anderson, L. (2017). The changing role of the health care customer: Review, synthesis and research agenda. Journal of Service Management, 28(1), 2–33.

Mehmood, R., Hunjra, A. I., & Chani, M. I. (2019). The impact of corporate diversification and financial structure on firm performance: Evidence from South Asian countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(1), 1–17.

Merici, M. A., Chariri, A., & Jatmiko, W. P. T. (2020). Value chain analysis for strategic management accounting: Case studies of three private universities in Kupang—East Nusa Tenggara. KnE Social Sciences, 4(6), 229–246.

Mrabure, K., & Abhulimhen-Iyoha, A. (2020). Corporate governance and protection of stakeholders rights and interests. Beijing Law Review, 11(1), 292–308.

Murphy, M. J., & Smolarski, J. M. (2020). Religion and CSR: An Islamic “political” model of CG. Business and Society, 59(5), 823–854.

Nair, S., & Nian, Y. S. (2017). Factors affecting management accounting practices in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Management, 12(10), 177–184.

Nuhu, N. A., Baird, K., & Jiao, L. (2023). The effect of traditional and contemporary management accounting practices on organisational outcomes and the moderating role of strategy. American Business Review, 26(1), 95–121.

Nur, M., Anugerah, R., & Indrawati, N. (2019). The role of internal corporate governance mechanism in accounting conservatism. Journal of Accounting Research Organization and Economics, 2(1), 63–70.

Olojede, P., & Erin, O. (2021). Corporate governance mechanisms and creative accounting practices: The role of accounting regulation. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 18(1), 1–16.

Ojra, J., Opute, A. P., & Alsolmi, M. M. (2021). Strategic management accounting and performance implications: A literature review and research agenda. Future Business Journal, 7(1), 64.

Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., & Hulland, J. (2018). Review articles: Purpose, process, and structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46(1), 1–5.

Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (pp. 33–61). Free Press.

Prasad, V. H., & James, K. (2018). Good corporate governance: Evidence from Fijian listed entities. International Journal of Finance and Accounting, 7(3), 76–81.

Qiu, F., Hu, N., Liang, P., & Dow, K. (2023). Measuring management accounting practices using textual analysis. Management Accounting Research, 58, 100818.

Raithatha, M., & Haldar, A. (2021). Are internal governance mechanisms efficient? The case of a developing economy. IIMB Management Review, 33(3), 191–204.

Ratnatunga, J., & Alam, M. (2011). Strategic governance and management accounting: Evidence from a case study. ABACUS, 47(3), 343–382.

Salemans, L., & Budding, T. (2023). Management accounting and control systems as devices for public value creation in higher education. Financial Accountability and Management, 1–19.

Seal, W. (2006). Management accounting and corporate governance: An institutional interpretation of the agency problem. Management Accounting Research, 17(4), 389–408.

Sehrawat, N. K., Kumar, A., Lohia, N., Bansal, S., & Agarwal, T. (2019). Impact of corporate governance on earnings management: Large sample evidence from India. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 9(12), 1335–1345.

Shank, J. (1989). Strategic cost management: New wine, or just new bottles? Journal of Management Accounting Research, 1(1), 47–65.

Shank, J. K., & Govindarajan, V. (1992). Strategic cost management: The value chain perspective. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 4(4), 179–197.

Shil, N. C. (2008). Accounting for good corporate governance. JOAAG, 3(1), 22–31.

Shil, N. C., Hoque, M., & Akter, M. (2014). Management accounting today: A perspective for tomorrow. Asia-Pacific Management Accounting Journal, 9(2), 37–68.

Siti, Z. A. R., Abdul, R. A. R., & Wan, K. W. I. (2011). Management accounting and risk management in Malaysian financial institutions. Managerial Auditing Journal, 26(7), 566–585.

Sloan, R. G. (2001). Financial accounting and corporate governance: A discussion. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32(1–3), 335–347.

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104(1), 333–339.

Snyder, H., Witell, L., Gustafsson, A., Fombelle, P., & Kristensson, P. (2016). Identifying categories of service innovation: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Business Research, 69(7), 2401–2408.

Solarino, A. M., & Boyd, B. K. (2020). Are all forms of ownership prone to tunneling? A meta-analysis. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 28(6), 488–501.

Strange, R., & Humphrey, J. (2019). What lies between market and hierarchy? Insights from internalization theory and global value chain theory. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(8), 1401–1413.

Sturgeon, T. J. (2002). Modular production networks: A new American model of industrial organization. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(3), 451–496.

Tang, J. Q. (2015). Science and technology information. Accounting Research, 2, 32–33.

Tian, Q., Liu, Y., & Fan, J. (2015). The effects of external stakeholder pressure and ethical leadership on corporate social responsibility in China. Journal of Management & Organization, 21(4), 388–410.

Torraco, R. J. (2016). Writing integrative literature reviews: Using the past and present to explore the future. Human Resource Development Review, 15(4), 404–428.

Trevisan, P., & Mouritsen, J. (2023). Compromises and compromising: Management accounting and decision-making in a creative organization. Management Accounting Research, 60, 100839.

Verlegh, P. W. J., & Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M. (1999). A review and meta-analysis of country-of-origin research. Journal of Economic Psychology, 20(5), 521–546.

Wells, H. (2010). The birth of CG. Seattle University Law Review, 33(4), 1247–1292.

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553.

Williams, J. J., & Seaman, A. E. (2010). Corporate governance and mindfulness: The impact of management accounting systems change. Journal of Applied Business Research, 26(5), 1–17.

Williams, J. J., & Seaman, A. E. (2014). Does more corporate governance enhance managerial performance: CFO perceptions and the role of mindfulness. Journal of Applied Business Research, 30(4), 989–1002.

Witell, L., Snyder, H., Gustafsson, A., Fombelle, P., & Kristensson, P. (2016). Defining service innovation: A review and synthesis. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2863–2872.

Wolf, T., Kuttner, M., Feldbauer-Durstmüller, B., & Mitter, C. (2020). What we know about management accountants’ changing identities and roles—A systematic literature review. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 16(3), 311–347.

Zou, J. J. (2019). Improvement of corporate governance structure and implementation of accounting standards. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7(1), 43–50.